Biography of the sculptor

LMAVB RS F320-923, lap. 1r

The sculptor-to-be was born on the 5th (17th) of November, 1827, in the city of Pinsk, the center of the Minsk province of the Russian Empire, in a palace, built with great care by her great-grandfather Mateusz Butrymowicz (1745–1814). For a long time it was believed that the artist was born in the estate of the Skirmuntt family in Kalodnaye (Калоднае), the present Stolin district, Brest county, Belarus. However, based on infomation from archival sources, this theory was disproved by the Polish historian Dariusz Szpoper.

LMAVB RS F320-941, lap. 1r

The information on Helena‘s father remains scarce. It is known that Aleksander Skirmuntt (1793–1845) was a marshal of the Pinsk County, the owner of Kalodnaye and the representative of the old noble family of the Pinsk region. The Skirmuntt family thought of themselves as descendants of Skirmuntt, the legendary Duke of Novogrudok. To emphasize their origins, they adorned their coat of arms, “Oak” (in Polish Dąb), with a duke‘s hat and mantle.

The mother of the sculptor, Hortensja Skirmuntt (1808–1894) was the daughter of Michał Orda, marshal of the Kobryn County (Кобрын, now Belarus) and Józefina Orda née Butrymowicz (1775–1859). Her brother was painter and composer Napoleon Orda (1807–1883).

LMAVB RS F320-942, lap. 1r

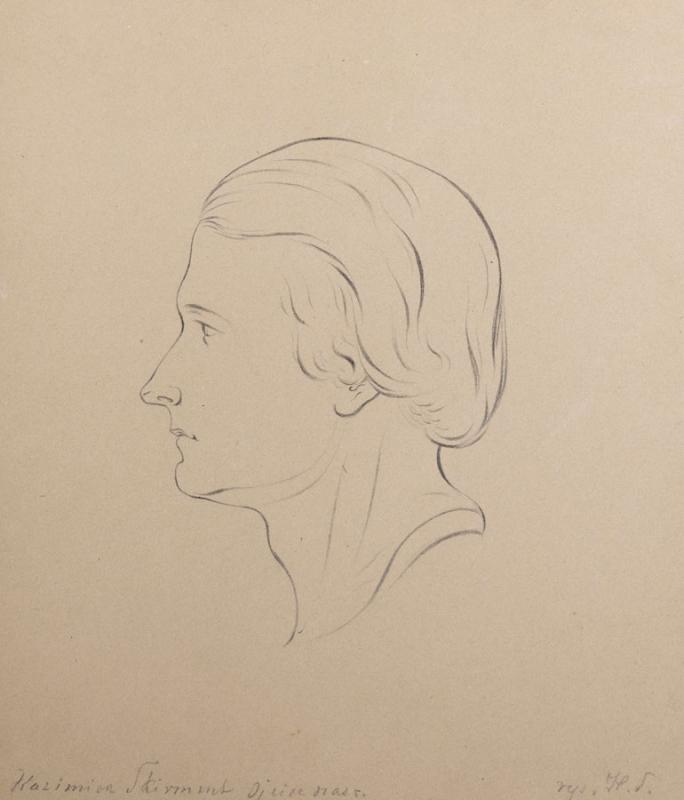

The only child, Helena was plagued by ill-health. Educated at home, from a young age she surprised her parents with unique artistic abilities and an attraction to drawing. At the age of thirteen, she was taken to Vilnius by her mother for a consultation with doctors, who strictly forbade Helena to read or strain herself in any other way but allowed her to study drawing. In Vilnius, Helena began to attend drawing and painting lessons with landscape painter Wincenty Dmochowski (1807–1862) but had to return home only after a couple of months. In April 1844, she went to Berlin with her mother to consult with ophthalmologists due to problems with her eyesight. While in Berlin, she attended private lessons with the German landscape painter Wilhelm Krause (1803–1864). After a two-month stay in Berlin, Helena and her mother decided to travel to Paris. Helena met her uncle Napoleon Orda and the Polish sculptor and graphic artist Władysław Oleszczyński (1807–1866), with whom she visited the Louvre. After viewing many priceless art collections, she herself started collecting old engravings and drawings. Helena Skirmuntt spent the winter of 1844–1845 in Dresden, studying painting with the German portrait painter Carl Christian Vogel von Vogelstein (1788–1868). In the spring of 1845, Helena returned to her native Polesia. Three years later, in 1848, she married Kazimierz Skirmuntt (1824–1893), a distant relative. He was the son of an influential industrialist and landowner Aleksander Skirmuntt (1798–1870) and Konstancja née Sulistrowska (1806–1845). He was educated in St. Petersburg University, at the Faculty of Natural Sciences. The newlyweds settled in the Kalodnaye estate. Three of their children were born here: Irena (c. 1849–1905), Konstancja (1851–1934), Stanisław (1857–1921).

LMAVB RS F320-929, lap. 1r

In 1850, Helena Skirmuntt and her husband, wanting to improve their health, visited the Druskininkai resort, where Helena first met and later became close friends with the amateur painter Jadwiga Kieniewiczówna (1825–1892). She encouraged Helena to meet the Visitandine nun Maria Czapska during a trip to Vilnius. Maria is believed to have had a significant influence on Helena’s Catholic beliefs and worldview. The friendship with these women served as a new impulse for Helena’s creative work. She became interested in religious painting, began to take care of documenting and preserving church heritage – she restored old paintings in Pinsk churches (together with the amateur painter Konstanty Radyko, former student of Wincenty Dmochowski) and liturgical vestments. In her drawings, she recorded figure compositions embroidered on a 16th-century chasuble.

In the autumn of 1852, at the urging of her mother and husband, Helena Skirmuntt travelled to Vienna to be treated at the clinic of ophthalmologist Friedrich Jäger von Jaxtthal (1784–1871). The doctor did not object to the patient’s work in art. Remembering how her uncle Napoleon Orda and Władysław Oleszczyński encouraged her to try her hand at sculpture, Helena decided to find a teacher. Unfortunately, sculptors in Vienna, still adhering to certain prejudices and gender stereotypes, were in no hurry to open their doors to her. As she was beginning to lose hope, the then little-known Austrian sculptor and medalist Josef Cesar (1814–1876) decided to help her. Helena underwent treatment for her eyes and stayed in Vienna to study for almost a year.

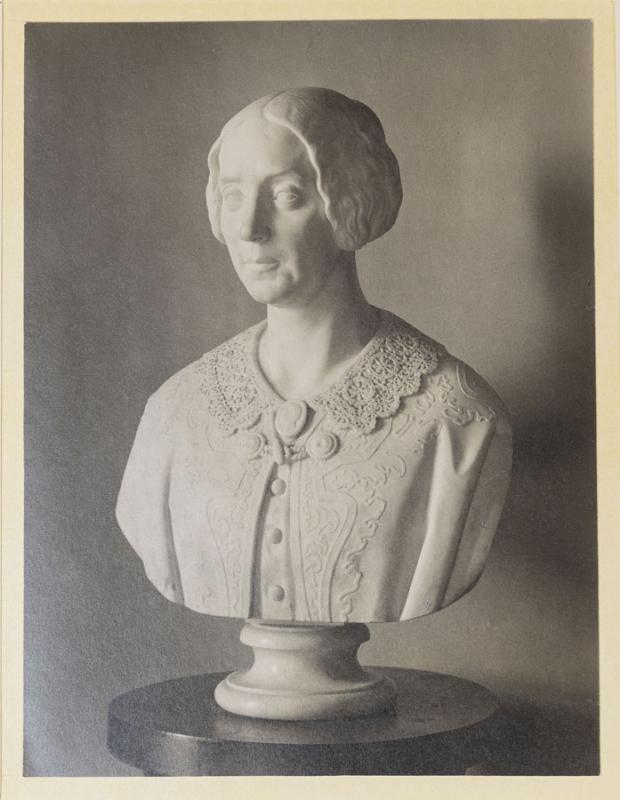

In the summer of 1853, Helena’s mother visited her, and on August 1 they left for another journey across Europe. On December 3, 1853, they arrived in Rome. Helena lived in the Eternal City until May of 1854. During this time, she met various painters, visited their homes and workrooms. She also met a Catholic priest and fiery preacher, publicist Hieronim Kajsiewicz (1812–1873). With help from Oleszczyński, Helena Skirmuntt was allowed to study intensively for several months under the tutelage of sculptor Pietro Galli (1804–1877). In addition, Helena made an acquaintance with Italian sculptor Luigi Amici (1817–1897), who offered to help create a marble bust of Helena’s mother. In October of 1854, Helena Skirmuntt returned to the Kalodnaye estate.

LMAVB RS F320-708, lap. 1r

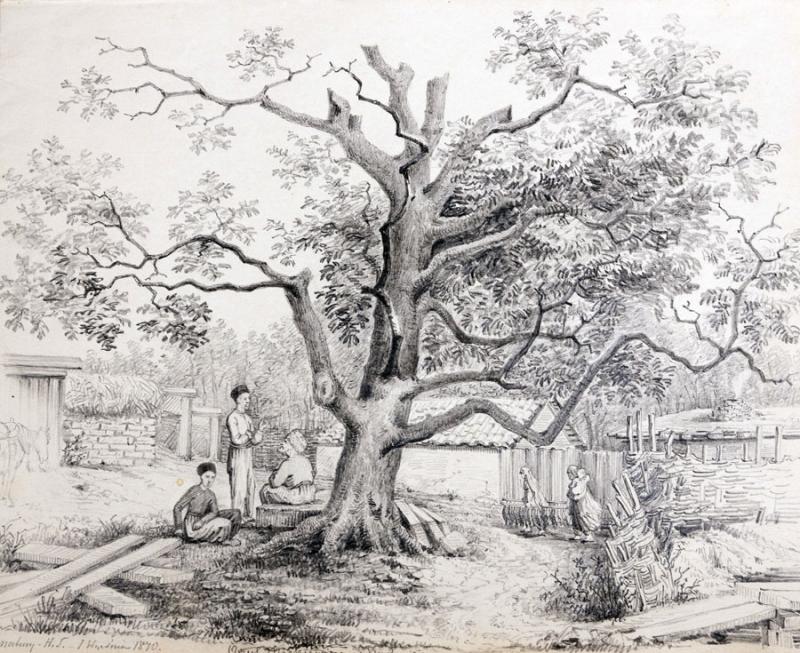

In the autumn of 1857, the Skirmuntt family moved to the nearby, but much quieter folwark near a lake in Rukhcha. The house was quite modest, but comfortable to live in. In one of the rooms with a large window facing north, Helena set up a sculpting studio where she could work undisturbed. However, the times were not favourable for arts. After the abolition of serfdom, the sculptor immersed herself in social work, education of village children. In November of 1862, with help from the peasants Helena built a huge cross on her property – a sign of liberation from serfdom.

The uprising of 1863–1864 disrupted the life of the Skirmuntt family. Helena’s husband, who refused the position of justice of the peace, was summoned to Minsk to explain himself and was consequently arrested there. After refusing to sign the apology addressed to the Russian Tsar for the uprising, he was sentenced and exiled to the depths of Russia, to the town of Kologriv, and later to Kostroma. A similar fate befell his wife. Helena Skirmuntt was tracked down and arrested while trying to deliver a letter from one of the local rebel commanders to General Romuald Traugutt (1826–1864). She was placed under house arrest and for several months stayed in a palace belonging to her mother in Pinsk. A verdict was delivered on September 30 (October 12), 1863. Helena was sentenced to exile to Tambov, the centre of a governorate in the Russian Empire. On October 17 (29), she left Pinsk, accompanied by two servants and a Russian officer with his soldiers, and reached Tambov on November 5 (17). A few months later, her husband was allowed to live in this city as well. In exile, Helena Skirmuntt kept a diary, the fragments of which were published in 1876 by her biographer Bronisław Zaleski (1820–1880). In June of 1864, Helena and her husband were ordered to move to a county centre, Kirsanov. They were also coerced to sell their estates (Kalodnaye Manor, and the Rukhcha folwark) in the Minsk province. In May of 1865, in Kirsanov, Helena Skirmuntt gave birth to her daughter Kazimiera (1865–1938), and a year later she received the news that on May 17 (29), 1866, Russian Emperor Alexander II announced a partial amnesty for the participants in the uprising.

In the spring of 1867, the Skirmuntt family were allowed to temporarily return to their homeland. They stayed briefly in Albrykhtov, the estate of Aleksander Skirmuntt, and began seeking permanent residence. As former exiles, they were still banned from settling in the western provinces of the Russian Empire, therefore Helena’s husband obtained permission to settle in the Crimean Peninsula, in Balaklava, on a farm previously purchased by his father.

Helena joined her husband in Balaklava with her daughters Konstancja and Kazimiera on September 5 (17), 1869. After settling in their new home, Helena Skirmuntt returned to more intensive creative work. She became interested in the past of Crimea, local customs, travelled to places that her beloved poet Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855) had gone to, and devoted a lot of time to reading in the winter evenings.

LMAVB RS F320-936, lap. 1r

In the summer of 1872, Helena’s health began to deteriorate. For a while, she was treated by Dr. Adolf Knott. On his recommendation, on December 14 (26), 1873, Helena left for the resorts of Southern France with her husband and daughter Konstancja. Helena suffered from fever, strong cough, and insomnia. They reached Marseille three weeks later. After she regained her strength, she left for the Amélie-les-Bains health resort at the foot of the Pyrenees mountains. She arrived there, but a week later, on February 1 (13), 1874, she died. After the relatives arranged the necessary documents, her remains were transported to her homeland and on October 2 (14), 1875, she was buried in the Catholic cemetery in Pinsk. The grave with the tombstone is extant to this day.

The Polish art historian Jolanta Polanowska categorizes the work of Helena Skirmuntt into several time periods: the 1840–1850s is the decade of a creative amateur in drawing and painting; the years 1852–1854 mark a period of sculpture studies in Vienna and Rome; the time of 1855–1861 consists of independent work in sculpture in her home in Polesia; 1861–1869 is the phase of reduced artistic activity due to political events, repression and exile; 1869–1873 are the years of intensive work in the Crimean Peninsula.

Until 1852, Helena Skirmuntt drew and painted landscapes, domestic scenes, portraits of family members, relatives and friends. In 1855–1856 she painted the altar picture "Immaculately Conceived St. Virgin Mary" for the St. Anne's church in Dūkštos (Vilnius district).

The larger and more important part of Helena Skirmuntt's work remains in sculpture. Helena created several dozen portrait medallions of her relatives, friends, well-known intellectuals, 4 crucifixes (1853–1871), 3 wax Paschal candles for the churches of Pinsk, Warsaw and Ruzhyn (Ukraine), portrait reliefs of Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas and King Mindaugas (1870). Her most famous work in sculpture is the chess set (1863–1873).

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 30r