Chess set: from the idea to the result

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 19r, nr. 1

The idea of creating the chess set came to Helena Skirmuntt when she was far from home. Convicted and exiled to Tambov for her connections with the rebels, Helena met the doctor and public figure Fortunat Nowicki (1830–1885). He told her a story about exiles being transported into the depths of Russia, often stuck in Tambov for a few days, who would mold "something like chess pieces" from bread or carve them out of wood, wishing to play some board game and thus lighten up their days of torment. Dr. Nowicki came up with a plan to help the convicts and offered Helena and her husband to contribute. He asked for them to create chess piece models that would be created by applying advanced technologies, namely, the method of Jewish-born German physicist and electrical engineer Boris Jacobi (Борис Якоби, Moritz Hermann von Jacobi; 1801–1874), invented in 1838 – electroplating – that would allow them to produce very accurate metal copies of the figures and distribute them to the exiles. The ambitious plan, as it turned out later, was doomed to fail due to the harsh conditions of their surroundings. However, the plan turned out to be positive in another way. Allowing Helena to share in his impulse of creativity, the doctor managed to improve the state of her mental and emotional well-being.

According to her biographer Bronisław Zaleski, Helena took up this work with great enthusiasm. Since these chess pieces were intended for the exiles, they required an inspiring ideological motif that would remind them of the glorious past, would rekindle patriotic feelings. The historic battle at Vienna, which inspired several generations of artists (for example, painters Marcello Bacciarelli (1731–1818) and Jan Damel (1780–1840)) served as a perfect basis for the theme of the chess set.

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 13r, nr. 1

After delving into the history of chess, Helena chose the original, Indo-Persian version of the game, which was different from the usual version in that it did not have female royal figures (Queens): here they were replaced by the Grand Crown Hetman and the Grand Vizier of the Ottomans. Helena’s vision of this chess set, unlike traditional sets of the game, where most of the pieces are identical (black and white pawns, pairs of rooks, knights, etc.), was to have every single piece different and unique. For this purpose, she extensively researched and collected all kinds of iconographic material relating to the weapons and clothes of the armies that had fought in the battle, looking for suitable prototypes and original solutions. Perfectionism, restriction of freedom, household concerns, health problems, family expansion (her daughter Kazimiera was born in May 1865) resulted in Helena’s creative process being very slow. In a letter to her friend Jadwiga Kieniewiczówna, she wrote about the chess pieces: “...it might be the best thing I have ever created...”. However, at the same time, she expressed her regret that she was not able to finish them. While living in exile, the sculptor created plaster models of just seven pieces.

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 13r, nr. 2

After moving to Balaklava in Crimea, Helena Skirmuntt began her work once again after a hiatus of several years, being encouraged to alter her vision and its audience by her brother-in-law, the owner of Shemetovo Manor, Konstanty Skirmuntt (1828–1880), who offered to finish the pieces, cast them from metal and sell them to any interested buyer. According to foreign experts, the price of a chess set at that time could reach a price of 1000 rubles. For comparison, the annual salary of a drawing teacher in Lithuania ranged from 120 to 200 silver rubles. “I never dreamed, my dear [...] brother-in-law”, Helena wrote in June of 1870, “that my work would gain any monetary value”. Since Helena was deeply religious and had a dream to visit the Holy Land since childhood, she jokingly called the supposed earnings for her chess figures “a passport to Jerusalem”. In any case, feeling the support of her relatives (mother, husband, daughter Konstancja) Helena accepted her brother-in-law’s challenge quickly. Soon there came a great opportunity to present her chess figures at the World Exhibition in Vienna. However, despite her greatest efforts, she did not have time to finish all the figures before this important event. Twenty figures were sent to Vienna. There, under the supervision of the Austrian sculptor and medalist Josef Cesar (1814–1876), the chess pieces were cast in bronze, polished, gilded, silver-plated and presented to the public for the first time.

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 14r, nr. 1

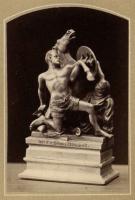

According to contemporaries, every piece of this historical allegory was a small masterpiece. The four most important chess pieces (Kings and Queens) instead immortalized different historical figures: the ruler of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Jan III Sobieski; Grand Crown Hetman Stanisław Jan Jabłonowski (1634–1702), Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, Mehmed the Hunter (Mehmed IV Dördüncü; 1642–1693) and Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa (Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Paşa; 1634/1635–1683). The other chess pieces depicted different types of soldiers and distinct social or ethnic groups. The following names were used: Squire, Flag-Bearer, Janissary, Tatar (for the bishops), Hussar, Knight, Sipahi, Ethiopian with the Moor (for the knights), Page, Lad, Field Camper, Polesian, Bashi-bazouk, Arnaut (for the pawns). The equivalents of the rooks depict animals with historical heraldic motifs: the Lion, a heraldic figure from the coat of arms of Red Ruthenia (the birthplace of Jan III Sobieski), holding a shield with the coat of arms of Cracow; the Bear, a figure from the coat of arms of Samogitia, holding a shield with St. Christopher (the coat of arms of Vilnius), and the Camel, carefully sketched from nature in the market of Simferopol, in autumn of 1870. It is not known what animal or heraldic figure Helena chose for the fourth rook. It is also unclear what the figures of the ten remaining pawns might have looked like. Helena was not able to finish them.

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 14r, nr. 2

According to researchers, this chess set is a unique example of historicism in sculpture, which also reveals the trends of Lithuanian sculpture in the middle and late periods of the 19th century: the minuteness of form, the romantic spirit leading to the depiction of great individuals, the interest in historical themes, the literary nature of imagery. It is unique that the artist was a woman, who had the courage to enter a field seen as exclusively male. Sculptors were seen as having to do messy and shameful physical labor, while working with the representation of the naked body was deemed inappropriate for the “weaker” sex. Helena became an example of success to future women sculptors.

LMAVB RSS A-974, lap. 27r, nr. 2