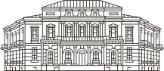

The Episodes of Kant's Everyday Life

Iš: https://www.lookandlearn.com/history-images/YR0626051/Portrait-of-Immanuel-Kant

Of all the portraits of Kant that have survived to the present day, there are not even two that resemble each other. Perhaps this paradox is explained by the fact that there were two Kants. The first is a short man with not the most beautiful features. The second is the „elegant magister” who charmed his interlocutors with his enchanting blue eyes and impeccable manners. In this portrait, the two Kants partly coincide. The man hunched over by the lectern is hardly handsome, but his total devotion to his work and his contemplative gaze give us a sense of the inner light that all those who had the opportunity to communicate with the philosopher recalled.

Iš: https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Königsberg_Castle.jpg

Kant spent most of his life in Königsberg. He was sure that this city was ideal for the life of a philosopher – after all, you can get enough knowledge here without travelling anywhere! In Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View he wrote: “A large city like Königsberg on the river Pregel, the capital of a state, where the representative National Assembly of the government resides, a city with a university (for the cultivation of the sciences), a city also favored by its location for maritime commerce, and which, by way of rivers, has the advantages of commerce both with the interior of the country as well as with neighboring countries of different languages and customs, can well be taken as an appropriate place for enlarging one's knowledge of people as well as of the world at large, where such knowledge can be acquired even without travel”.

Iš: https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kant_wohnhaus_2.jpg

In 1784, Kant bought a house on Prinzessinstrasse near Königsberg Castle. It seemed that he had finally found a quiet place where he could devote himself entirely to his work. However, Kant soon encountered a number of problems that disturbed his contemplative lifestyle for some time. When Kant bought his new house, he probably didn't mind that there was a prison next door. However, problems arose from where he least expected them. It was not that he was not bothered by the bad behaviour of the prisoners (apparently there was nothing wrong with them), but rather that he was prevented from working ... by the excessive piety of the criminals. In summer, when the church windows were open, the whole neighbourhood could hear the loud prisoners' choir. For the philosopher, however, these sounds made it difficult to concentrate. With the help of his friends from the magistrate's office, he managed to cope with this problem. The windows in the church were forbidden to be opened, and the prisoners were ordered to sing more quietly (Kant was sure that the reason for their zeal was not piety, but a desire to curry favour with their superiors). But his troubles did not end there. In the evenings, the philosopher liked to look up at the Löbenicht belfry. However, as the trees in his neighbour's garden grew, they blocked his view. Only after begging his neighbour to trim his trees regularly was he able to regain his peace of mind. In the end, though, there was only one problem that Kant could not cope with – the boys got into the habit of shaving the stones in his garden. Even the police could not do anything, so Kant almost stopped visiting his own garden.

Stoa Kantiana iš: Witt, August. Die dritte Jubel-Feier der Albertus-Universität zu Königsberg. Königsberg: Verlag von Theodor Theile, 1844.

LMAVB 5272108

Immanuel Kant was a graduate and later a teacher of the University of Königsberg, which was the alma mater of many famous Lithuanian writers: Martynas Mažvydas (before 1520–1563), Jonas Bretkūnas (1536–1602), Danielius Kleinas (1609–1666), Jokūbas Brodovskis (1692–1744) and Kristijonas Donelaitis (1714–1780). Martin Liudwig Rhesa (1776–1840), who was interested in Lithuanian culture, was also Kant's student – he even dedicated a poem to him, which is not surprising as Kant was known as an interesting and charismatic professor, adored by his students. Kant himself loved to teach and knew that students will work hard if they are really interested in the subject: “But, as to studying too hard, there is no need to warn young people. With regard to studying, youth needs spurs, rather than reins. <…> Anxious parents, however, have nothing to fear from overtaxing the industriousness of young people (as long as their minds are otherwise sound). A student is protected by Nature from such overloading with knowledge by finding subjects distasteful, over which he only broods and breaks his head to no avail”.

Iš: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Löbenicht#/media/File:ID003564_A465_NeuerMarkt.jpg

The main publisher of Immanuel Kant's works was Johann Friedrich Hartknoch (1740–1789). In Riga, he published Kant's most famous works: Critique of Pure Reason (1781) and Critique of Practical Reason (1788). J. F. Hartknoch became interested in the book trade thanks to his teacher, the printer Johann Jakob Kanter (1738–1786) and from 1760 his bookshop was a popular meeting place for intellectuals. Kanter was a great admirer of Kant, he had a painted portrait of him hanging in his bookshop, and Kant even lived in Kanter's house for a while.

Iš: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/25/Kant_doerstling2.jpg

Kant was sure that “Eating alone (solipsimus convictorii) is unhealthy for a philosophizing man of learning”, that is why he never did. At the same time, however, he didn't like large gatherings. Indeed, Kant had only six sets of cutlery – that was the maximum number of people he would entertain at one time as he was convinced that, in order for the conversation to be interesting for everyone, there should not be too many guests. It was these conversations that made Kant's dinners famous. In Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View he formulated the following rules, which meet the requirements of good dinner conversation: ,,A tastefully arranged dinner that animates the company obeys the following rules: a) choose topics for conversation which interest everybody, and always give everyone a chance to add something appropriate; b) do not allow deadly silence to fall, but permit only momentary pauses in the conversation; c) do not change the subject unnecessarily, nor jump from one subject to another <...>. If the mind cannot find a connecting thread, it feels confused and realizes with displeasure that it has not progressed in matters of culture, but rather regressed. An entertaining subject must nearly be exhausted before one can pass on to another; and, when conversation stagnates, one must know how to suggest skillfully, as an experiment, another related topic for conversation. In such a way one individual in the company can direct the conversation, unnoticed and unenvied”.

Iš: https://lt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liudvikas_Rėza#/media/Vaizdas:Liudvikas_Rėza.jpg

Among Kant's students was the well-known publisher of Lithuanian writings, Martin Ludwig Rhesa (1776–1840). After the death of his teacher, he wrote a dissertation devoted to one of the problems of his philosophy (De librorum sacrorum interpretatione morali e Kantio commendata). In the aforementioned dissertation, he wrote: “I have never regretted having had such teachers as Kant, who explained philosophy in a subtle way <...>”. After Kant's death, M. L. Rhesa dedicated one of his poems to him (“Elegy to Immanuel Kant”). Prutena (a two-volume collection of poems prepared by Rhesa in 1809 and 1825) contains other poems mentioning Kant as well as other famous professors of the University of Königsberg.

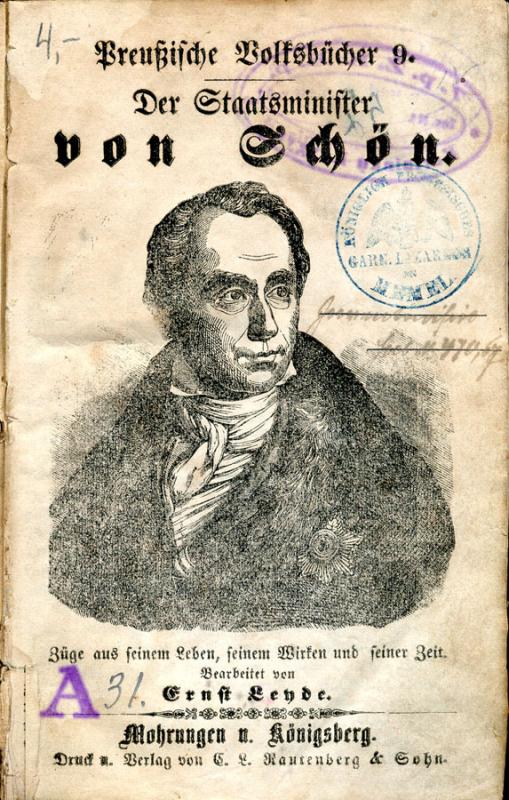

LMAVB 374662

Kant's teachings and his concept of the categorical imperative shaped the worldview of, among others, Heinrich Theodor von Schön (1773–1856), a Prussian statesman and senior president of the West and East Prussian provinces. H. T. von Schön himself called Kant his great teacher, once writing: “Without Kant's philosophy and sauerkraut soup I would have died long ago”. It is also interesting to note that, when Schön was a student at the Law Faculty of the University of Königsberg, the plan for his first semester of studies was drawn up by Kant, who was a friend of Schön's father.