St. Jerome and His Images in Books

St. Jerome (circa 347-420) is a Christian theologian, a Church Father, priest, and translator of the Holy Scripture into Latin. Born in about 347 in Stridon, Dalmatia, he is also called Jerome of Stridon or Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus. Jerome studied grammar and rhetoric, Roman literature and the basics of Greek in Rome, where he also received Baptism in 366. After having lived for a while the life of a recluse in the desert of Chalcis, he was ordained into priesthood in 377. The future Saint studied under Gregory Nazianzen and was a secretary to Pope Damasus I. It was probably the latter that encouraged Jerome to edit the old Latin translation of the Gospels. With the death of the Pope in 384, Jerome lost both his patron and the hope to become his successor, and so was forced to leave Rome. After making a pilgrimage to Egypt, he settled in Bethlehem. There Jerome translated most of the books of the Old Testament (it must be acknowledged that this translation was not consistent, not all the books of the Holy Scripture were uniformly accurately translated). In Bethlehem he also wrote commentaries on almost all the books of the Old Testament, in which fragments of the then exegetical literature survived to these days. Jerome’s legacy also includes dogmatic and polemical texts against heretics of the times, hagiographical and historical works, letters. Jerome died on September 30, 420, the day which is now celebrated by the Catholic Church as his Feast (the Orthodox Church has it on June 15). Officially, the cult of St. Jerome was confirmed only in the 18th century (he was beatified by Pope Benedict XIV in 1747 and sanctified by Pope Clement XIII in 1767), but already shortly after his death, there started talks about his saintliness and miracles occurring with his intercession. In the 7th century, he was proclaimed one of the four Fathers of the Western Church along with Augustine, Ambrose, and Gregory the Great.

The Holy Scripture transcribed in the 13th century in the environment of Paris University begins with St. Jerome’s letter featuring a decorated initial, in which the illuminator drew the very author of the letter wearing a monastic habit and leaning over his writing. The habit is the clothing characteristic for St. Jerome as depicted in the earliest portraits of him.

The title of this book, Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia, or the Bible of St. Jerome, is from a much later period than the manuscript itself. The Vulgate does not contain any information as to who and when transcribed it. The title was added in an empty leaf at the end of the manuscript much later, in 1446.

This prayer book, written in 1524 and owned by Sigismund the Old, contains a portrait of St. Jerome clothed in a cardinal’s robe. This portrait image begins the Psalms of St. Jerome so entitled in the honor of the translator of the psalms into Latin. The clothing of the Saint here symbolizes his closeness with and service to Pope Damasus I. However, St. Jerome never was cardinal, as this rank did not yet exist in the Church of his times. Nevertheless, the image of the translator of the Vulgate as a cardinal was widespread in the age of Renaissance. In decorating this manuscript, the illuminator, Cistercian monk Stanisław Samostrzelnik (~1480–1541), used the composition of Dürer’s engraving depicting St. Jerome. In 1510–1530, Samostrzelnik was chaplain and court artist to the Grand Chancellor, Krzysztof Szydłowiecki, 1467–1532), and later had his own workshop in Cracow, working as an illuminator of manuscript books and muralist. He illuminated this manuscript in 1524. In the 17th century the book was supplemented by new prayers.

The original of the manuscript is kept in the British Library.

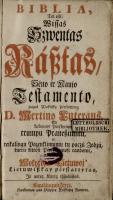

Bayerische StaatsBibliothek München, Rar. 330, antraštinis puslapis [BSB-Ink V-261 - GW M50899].

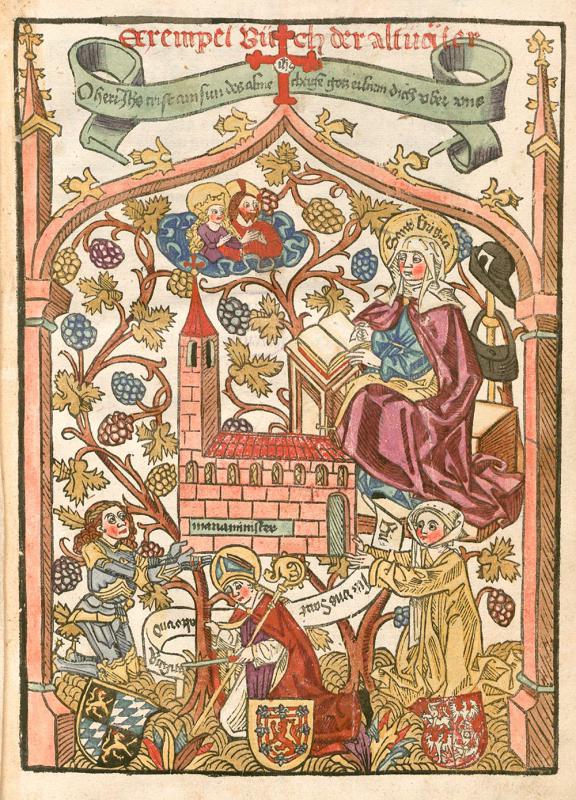

“Lives of the Fathers” printed in the 15th century are important for us not only because of their author, to whom this exhibition is dedicated, but because of the individuals depicted on the title page: George the Rich, Duke of Bavaria (1455-1503) and his spouse, Hedwig Jagiellon (1457–1502), the daughter of Casimir Jagiellon, granddaughter of Jogaila and sister of St. Casimir. At her feet, in the bottom right corner, there is a shield with the Vytis of Lithuania and the Eagle of Poland. This is the oldest example of the coat of arms of Lithuania known in print.

The title page shown here is from the incunabulum kept in the National Library of Bavaria.

LMAVB RSS V-16/1-1364

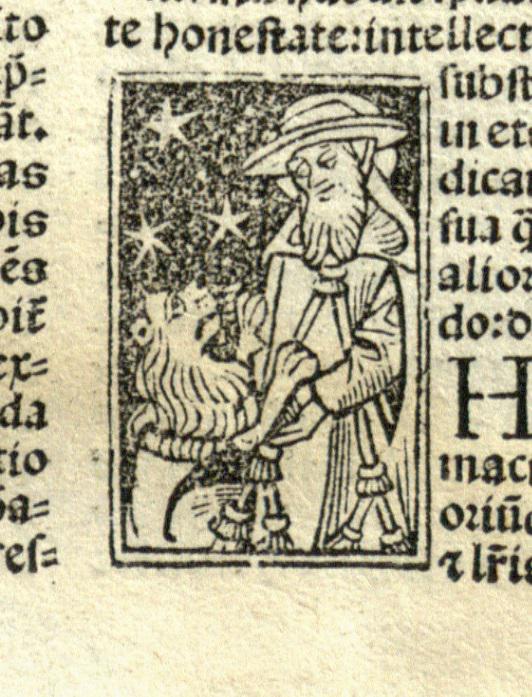

“The Golden Legend” by Jacob of Voragine is a collection of the lives of saints first written down in the Middle Ages and spread in manuscripts and later, in print books. Here, we see St. Jerome with a lion as portrayed in 16th-century literature.

A legend tells that a wounded lion, roaring in pain, attacked St. Jerome and the monks who accompanied him in a Syrian desert. Jerome, unafraid, removed a thorn from the beast’s paw and healed it. He tamed the lion so well that it never left the Saint’s side from then on. That is why lion became a particularly frequent attribute in the iconography of St. Jerome and acquired a complex semantic meaning. Jerome embodied the source of Salvation, while the lion embodied death and sin, from which one is saved at baptism as if removing the thorn. The King of the Beasts also had the meaning of victory over passions and sins, not unfamiliar to the restless Biblist. In the second half of the 15th century – first half of the 16th century, depicting the figure of St. Jerome in cardinal’s robes with a lion standing upright on its hind legs, leaning against the saint affectionately. This behavior, more common in a dog, not only emphasized the lion’s absolute devotion, but also served to remind of miraculous powers possessed by the Saint.

LMAVB RSS V-17/2-28

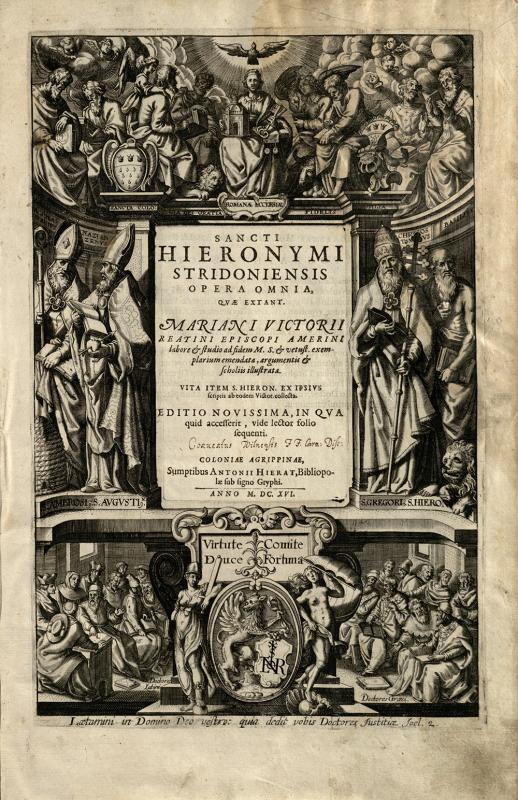

The title page in the first of the ten volumes of St. Jerome’s collected works is decorated by the portraits of the four Great Fathers of the Church. St. Jerome is depicted here together with St. Ambrose, St. Augustine and Pope Gregory the Great.

Jerome is recognizable not only from the caption under his image, but also from the lion at his feet, his usual attribute in art.

LMAVB RSS V-17/1401

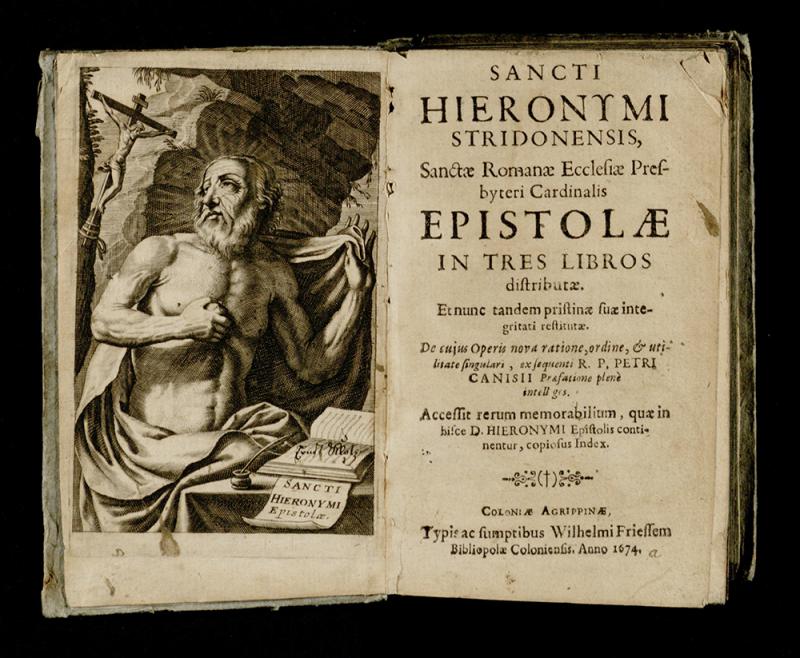

The frontispiece of this edition of St. Jerome’s letters features a monk praying in a cave. It is told that when Jerome with his followers came to Bethlehem, he founded there four monasteries, one for men and three for women. However, he himself went to live in a naturally formed grotto (probably this is the one depicted in the book) descending to the Grotto of the Nativity of the Lord.

LMAVB RSS V-17/2-243

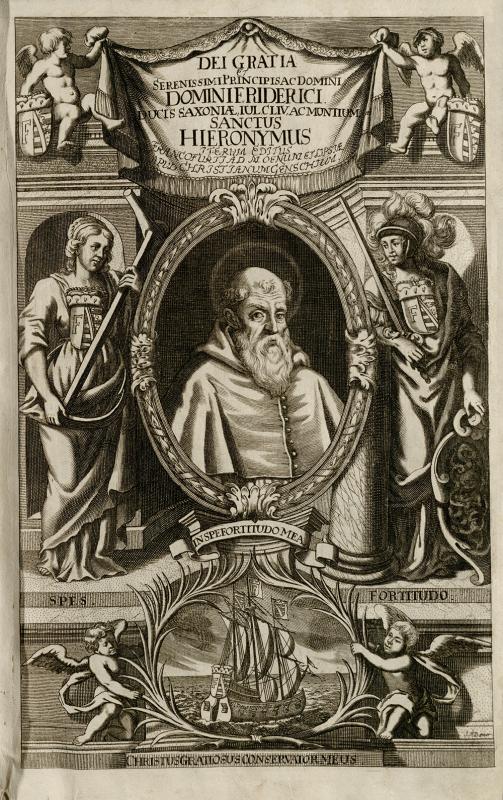

This edition of collected works of St. Jerome begins with a frontispiece featuring, in the center, a portrait of the author of the works, and the caption below the portrait, “In spe fortitude mea” (my strength is in hope), is illustrated by the allegorical figures of Hope and Strength depicted nearby.

The Catholics in Lithuania were not able to learn about St. Jerome from Lithuanian-language texts until relatively late in history, the description of his life was translated into Lithuanian and published in this language only in the 19th century. Before that, people would have seen him in church paintings and sculptures. However, the libraries of magnates and clerics contained a considerable number of old writings of St. Jerome: in the early 16th century, the Chancellor of Lithuania, Albertas Goštautas (Olbracht Gasztołd), owned Vitas partum, St. Jerome’s volume on the lives of Desert Fathers, while Mikalojus Daukša had Epistolae et tractatus published in 1495 in Nuremberg, etc. Moreover, Daukša, like many other translators, when translating the postilla, used the greatest work of this vir trilinguis (i. e. “trilingual man” fluent in Greek, Latin and Hebrew) – the Vulgate. The more educated Catholics who could read in Polish were able to read the Life of the St. Jerome in “The Lives of Saints” by Piotr Skarga (1536–1612), the first rector of the Vilnius Jesuit Academy. This work was written in 1577 and first published in Vilnius in 1579 under the title “Zywoty świętych”. Already in the author’s lifetime, the lives of saints were printed eight times in Lithuania and Poland. Mikalojus Kristupas Radvila (Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł) the Orphan (1549–1616) also wrote about St. Jerome, describing how, during his journey to Jerusalem, he visited the cell of the Saint.

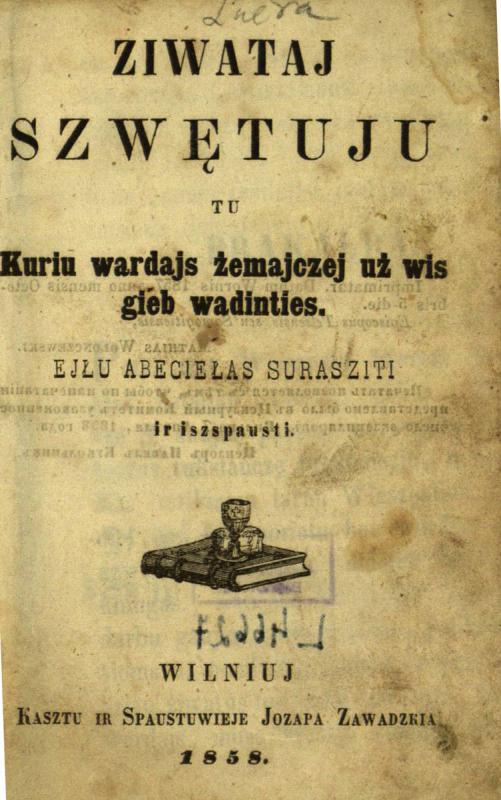

The Life of St. Jerome in Lithuanian for the first time appeared in the “Ziwataj szwętuju” compiled by Bishop Motiejus Valančius and published in 1858 by the Juozapas Zavadskis Printing House in Vilnius. It should be noted that this text gives an incorrect date of death for St. Jerome, 422 instead of 420. In a later such work, “Giwenimai szwentuju Diewa” by Serafinas Laurynas Kušeliauskas, the Life of St. Jerome is already omitted. However, he is cited as an authority in the chapter “Szłowe Szwentuju”, which contains explanations on why it is necessary to know, remember and worship the Saints.

LMAVB RSS L-16/2-3

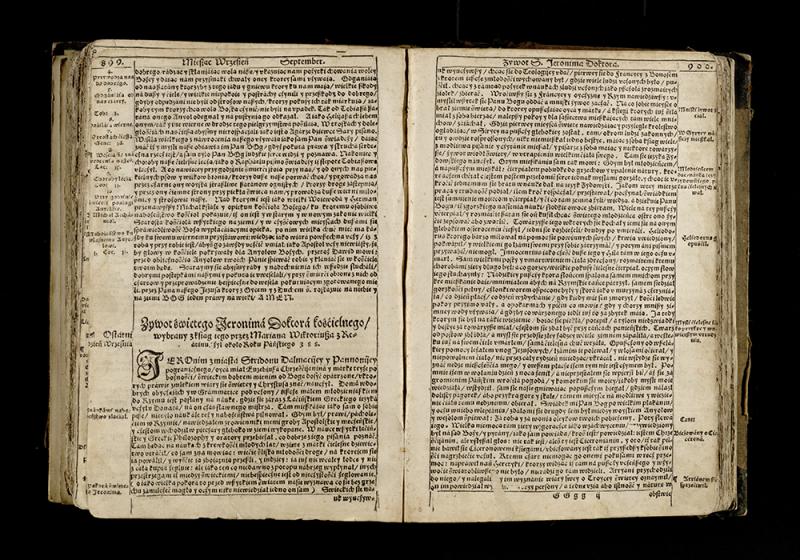

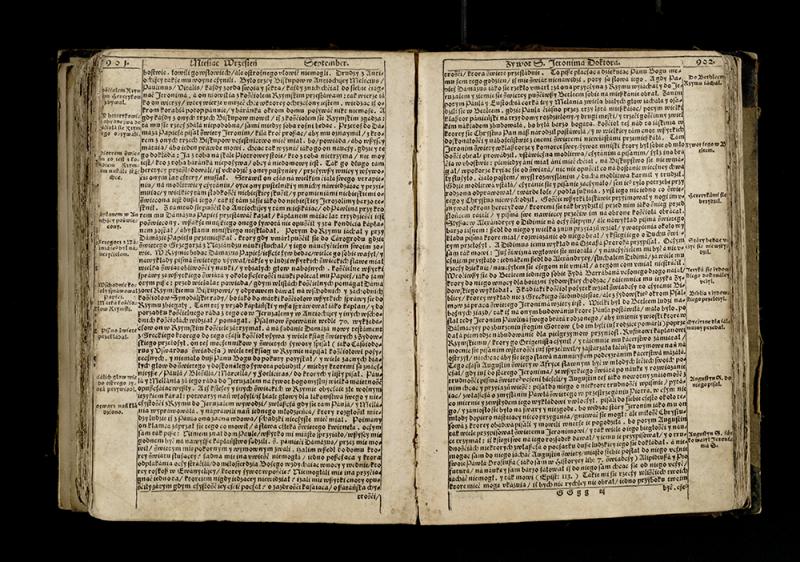

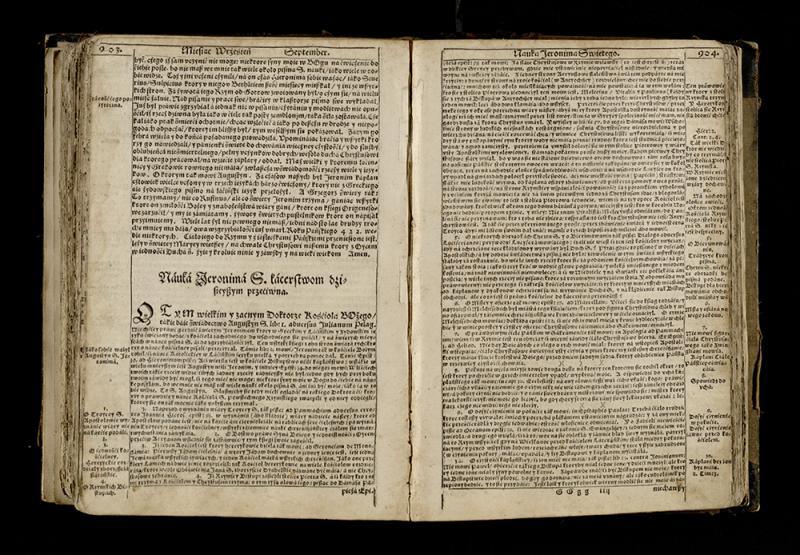

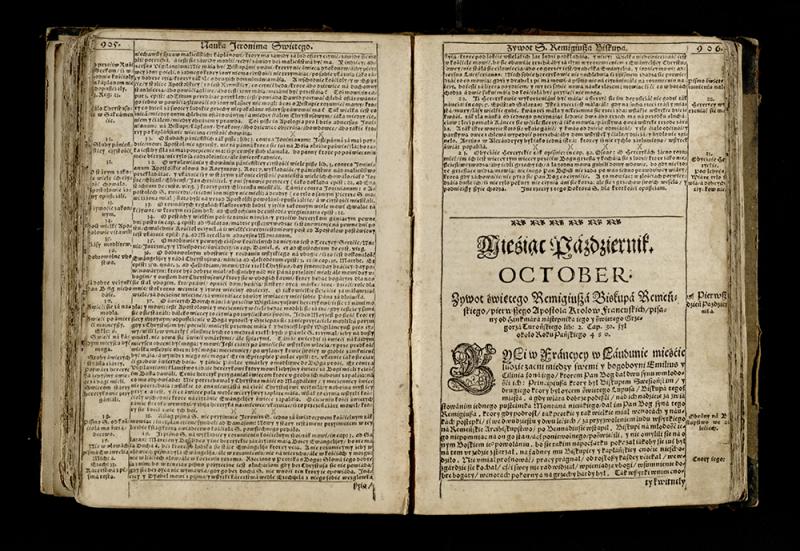

The Life of St. Jerome recounted by the Jesuit Piotr Skarga in “The Lives of Saints”. All the lives are arranged according to calendar, by days dedicated to one or another Saint. The day assigned for reading about St. Jerome is September 30 as this is his Feast day in the Catholic liturgical calendar.

This book is the first edition of “The Lives”, printed in the printing house of Mikalojus Kristupas Radvila in Vilnius.

LMAVB RSS L-17/2-59

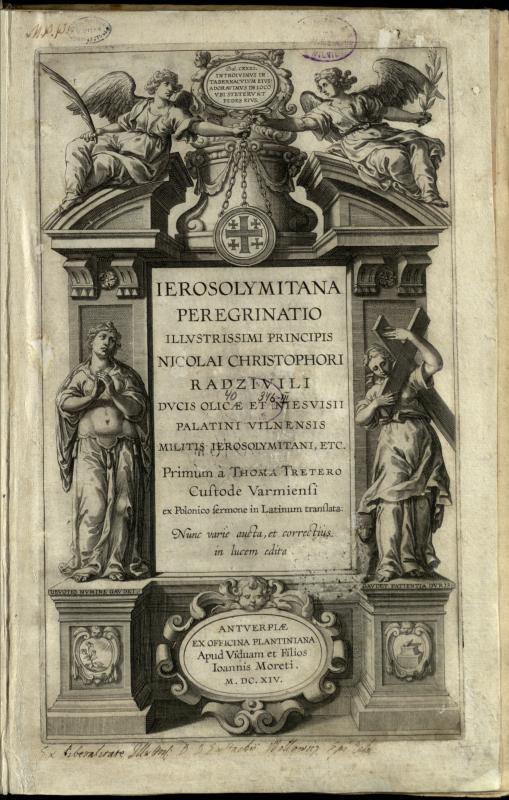

In 1583, Mikalojus Kristupas Radvila (Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł) the Orphan (1549–1616) made a visit to the cell of St. Jerome in Bethlehem. He described what he had seen in the book “A Journey to Jerusalem”:

On the left, there is another cave, in which there are three monuments. Right when you come in, the first on the right is for St. Eusebius, the second on the left is for St. Paula, and the third, for St. Jerome.

(…)

From those subterranean crypts one climbs into the room of St. Jerome, where he translated the Bible. It is very dark, being located right under the church, into which this holy man would climb the stairs that still exist nowadays, and then he would enter a door which has by now been bricked up. Some light comes in from the monastery through a tiny window.

(Quoted from: Radvila, Mikalojus Kristupas, Našlaitėlis. Kelionė į Jeruzalę (A Journey to Jerusalem) / Translated from Latin by Ona Matusevičiūtė. Vilnius: Mintis, 1990, p. 100–101.

epaveldas.lt

The Life of St. Jerome, first recounted in the Lithuanian language in “Ziwataj szwętuju” (“The Lives of Saints”) (p. 113–117)

The publisher Serafinas Laurynas Kušeliauskas (1820–1889) cites St. Jerome as one of the leaders of the Church and explains in the preface to his lives of saints why people should read such books and learn from them (p. 10–11).

![Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia [Paryžiaus Biblija]. Prancūzija, XIII a. Pergamentas. Lotynų k. Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia [Paryžiaus Biblija]. Prancūzija, XIII a. Pergamentas. Lotynų k.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/453755a8cf53af6e81169b927136f935882a1786.jpg)

![Giwenimaj szwentuju Diewa. [Sudarytojas Serafinas Kušeliauskas]. Wilniuje: kasztu ir spaustuwieje Juozapa Zawadzkia, 1862 [i. e. 1887]. Giwenimaj szwentuju Diewa. [Sudarytojas Serafinas Kušeliauskas]. Wilniuje: kasztu ir spaustuwieje Juozapa Zawadzkia, 1862 [i. e. 1887].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/8bcf05de4bcd946d40b73f4c08f410e9d6817452.jpg)