The Holy Scripture and Its Translations

The original text of the Holy Scripture was written in several languages – the Old Testament, in Hebrew and Aramaic; the New Testament, in Greek. As its books were written in different times and intended for individual communities, they reflected the language of orally disseminated stories of the times.

At those times when at least some members of a religious community had trouble comprehending the language of the Holy Scripture, there would arise a need to translate a text, to write down in a local language. As early as in the 3rd–2nd century BC, the Old Testament was translated into Greek. This translation is known by the name of Septuagint. A legend connects it with the pharaoh Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 b. C.). The Babylonian Talmud and other texts tell that the pharaoh hired 72 Jewish wise men (6 each from the 12 tribes of Israel), locked them all in separate rooms and ordered to translate the Torah. Then a miracle occurred – by God’s will, all the translations were identical. The Latin name septuaginta (seventy), based on this legend, became widespread only in the time of Augustine of Hippo. It was the first translation of the Bible into Greek, and it later became part of the canon of the Christian Bible.

A particularly large number of translations of the Holy Scripture emerged with the spread of Christianity. The translations were necessary for a successful dissemination of the faith. In the late 4th century, translation of the Bible to various regional languages began. At the end of that century, St. Jerome made his translation into Latin, and a translation into Gothic appeared at about the same time. In the 5th century, the Bible was translated into Armenian, Syrian, Georgian, Coptic, and Ethiopian. In the Middle Ages, the number of translations dropped, even more so that Pope Innocent III, seeking to thwart heresies spreading among the Christians, forbade unapproved translations in 1199. Nevertheless, in those times the Holy Scripture or its parts were translated into Old English and French, Czech, Hungarian, and other languages. In 863, Cyril and Methodius started on their translation of the Bible into Church Slavonic.

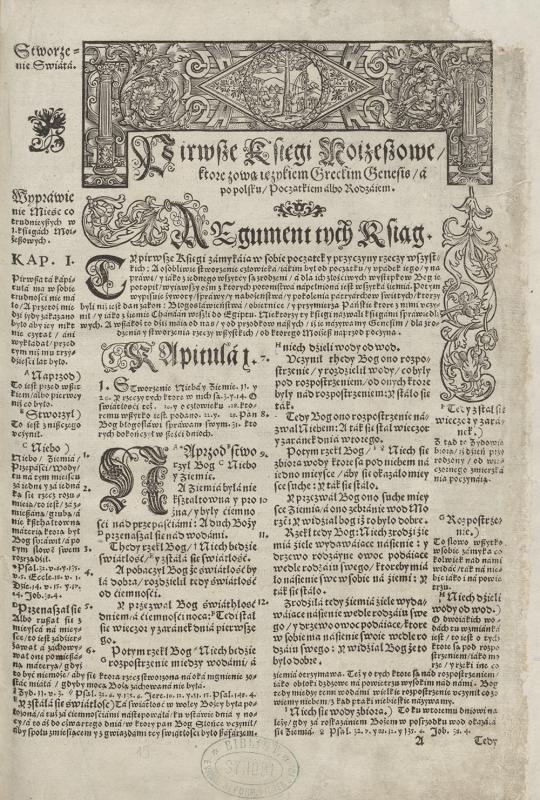

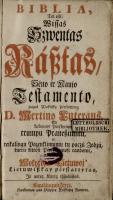

The dissemination of Bibles grew more intensive with the emergence of movable print (even the first printed book was the Bible printed in Mainz in 1455 by Johannes Gutenberg). Incunabula included texts of the Holy Scripture not only in Latin, but also in Hebrew, Italian, German, French, Catalan and Czech. The Reformation prompted an increase in number of translations into regional languages. Francysk Skaryna published “The Ruthenian Bible” in Prague in 1518-1519, the New Testament translated by Martin Luther into German appeared in 1522, the Dutch Bible in 1526, the French in 1530, etc.

There were also published various scientific editions of the Holy Scripture: multilingual Bibles that contained parallel text in an original language (or in Latin) and the language of the translation; Latin Bibles with commentaries; Bibles published in one of the original languages with the translation into Latin. Everyone who was literate could find a version of the Bible suitable for their needs.

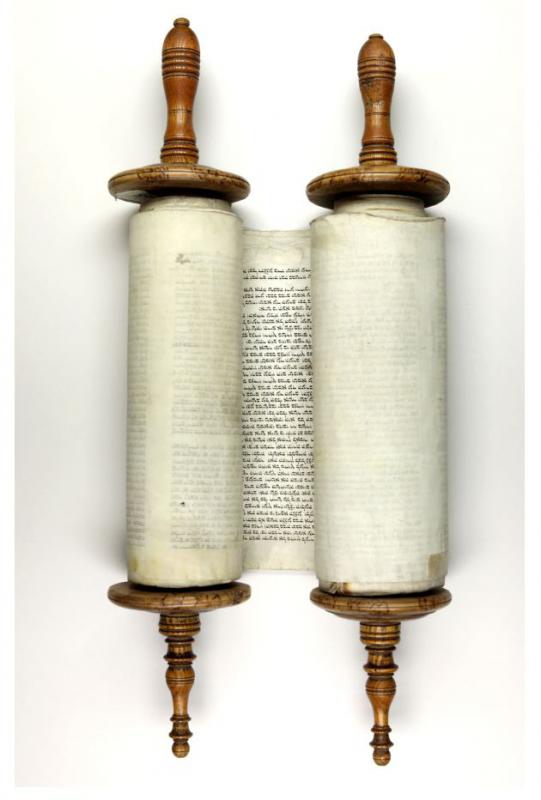

LMAVB RS F5-62

The text of the Pentateuch is written on parchment, in columns, from right to left.

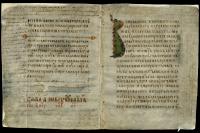

The Turov Gospel is a selection from the Gospels for holidays written in the 11th century. Only one its fragment is extant today. This is the earliest example of written culture kept in Lithuania. The manuscript is named after Turov (near Minsk, the present-day Belarus): the place where it was discovered in 1865 by a teacher called Nikolay Sokolov, in a coal box, during an archaeographic expedition.

The book also contains handwritten inscriptions from the early 16th century attributed to Prince Konstantin Ostrogiški (Konstanty Ostrogski, circa 1460–1530).

For more on the book, please see the exhibition “The Gardens of Mnemosyne”.

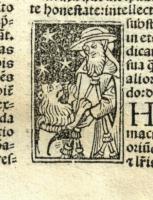

Old manuscript books usually did not have title pages. This Bible begins from a text whose title is highlighted by red font and by an initial decorated with a miniature featuring, in the center, St. Jerome writing.

This manuscript Gospel was found in the church of Zhuchavichy (Novogrudok District, Belarus). The photograph features the first page of the Gospel of Mark.

The book contains the texts of all the four Gospels, with instructions on what part of the text should be read at what time during a liturgy.

The 500-years-old Nobel Gospel was made on a commission by the Khvoensk starost, Semion Batyevich. Transcribed by deacon Sevastian Avvraamovich, it was finished “in June, on the first day of the month, on St. Justin’s Day, the Day of Justin, Philosopher and Saint Martyr”. The Gospel was donated to St. Nicholas Church in Nobel, a settlement in the Pinsk county.

The cover of the Gospel features the scene of the Crucifixion of Jesus, the corner plates carry engravings depicting the Four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

The very first book printed with movable type was the Bible. A considerable number of Bibles was published in the 15th century. This attests to the increasing demand for such books, and to great numbers of people who wanted to and could read the Holy Scripture in Latin. This book is barely 30 years younger than the first printed Bible by Gutenberg.

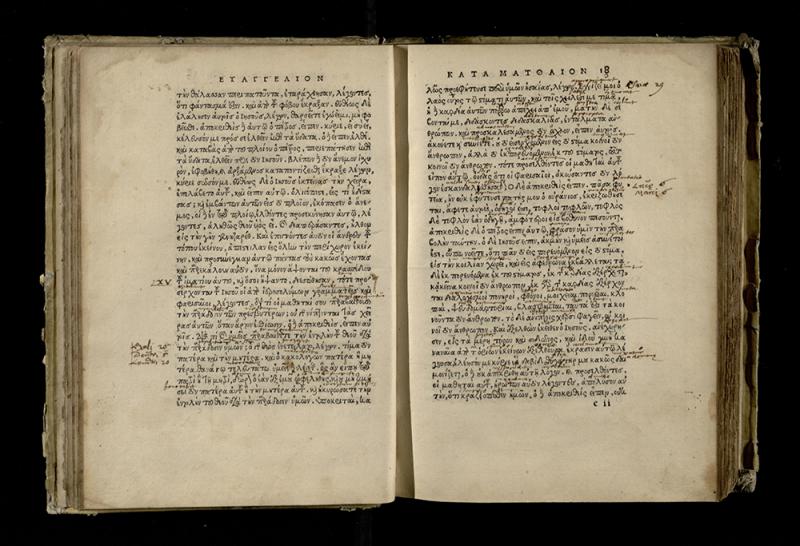

Some books are copiously marked by notes by the previous owners, including references to other places in the text of the Holy Scripture, translations and various comments.

Some of the first printed Bibles were copiously decorated by hand-drawn illuminations, others just had decorative or, sometimes, very plain, initials handwritten in the text. This Czech-language Bible, printed in the 15th century in Prague, has very few decorative initials (for example, in the beginning of the Gospel of Mark). The others are plainly written in colored ink. Next to such a letter, we can discern another, tiny, letter printed as a placeholder in the empty space left for the oversized initial so that the illuminator would not have to read the text in order to learn what letter should be drawn in a certain place. This tradition of leaving a placeholder in the empty space left for an ornamental letter came from manuscript books, when the scribe would similarly inscribe a tiny letter as a reference for the illuminator.

In 1517-1519 in Prague, Francysk Skaryna (before 1490 – before 1552) published the separate books of the Old Testament known as “The Ruthenian Bible”. Later, before 1522, he came to Vilnius, where he founded a printing house. This was the first printing house in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and the first books published there, “The Little Traveler’s Book” (circa 1522) and “The Apostle” (1525), also contain translations of the Bible into Church Slavonic intended to be read by the Orthodox Christians. “The Little Traveler’s Book” consists of the psalms of the Old Testament and other liturgical texts, and “The Apostle”, of writings and letters of the Apostles of the New Testament.

For more on Francysk Skaryna and his Bible see the virtual exhibition “The Ruthenian Bible of Francysk Skaryna turns 500”.

This New Testament book printed in the original language, Greek, contains numerous commentaries in Latin and Greek left by an unknown 16th-century reader. The front endleaf had a Latin inscription to the point that this is a rare edition allegedly used by Luther himself. As the book used to belong to the Gotthold Library in Könisgsberg, and an even earlier owner had deemed it important to mention that it had been used by Martin Luther, it may be guessed that this owner was one of the Evangelicals.

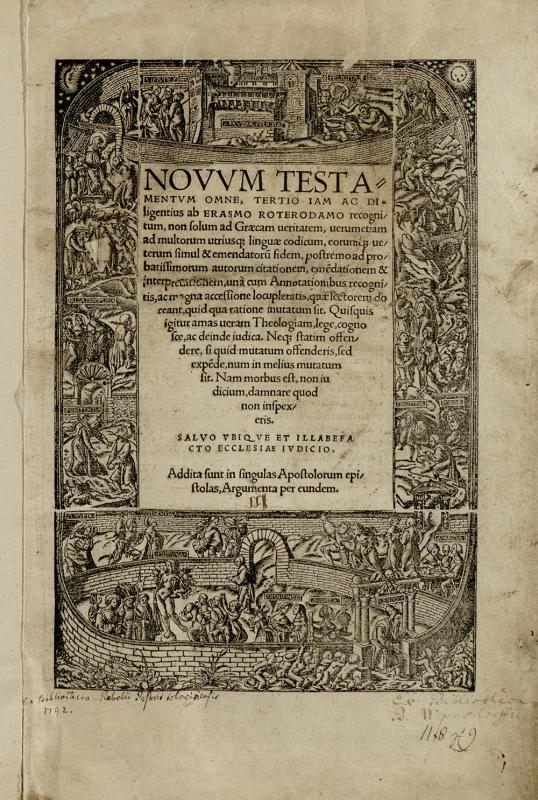

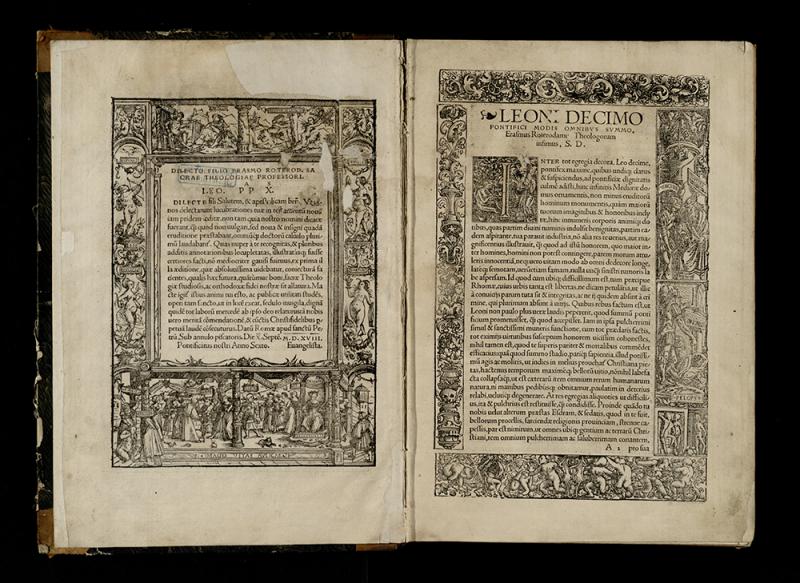

A Latin translation of the New Testament by Erasmus of Rotterdam (1469–1536) with his commentaries and the Greek text original.

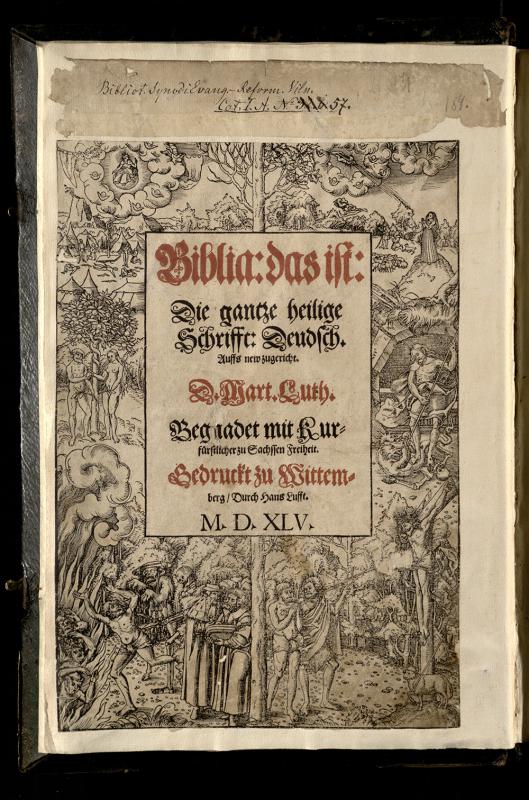

With a view to as many people as possible being able to read and understand the text of the Holy Scripture, translators attempted to use as common a language as possible and to avoid vernacular forms. Owing to this aspiration towards universality, the Bible translated by Martin Luther laid foundation for the standard German language.

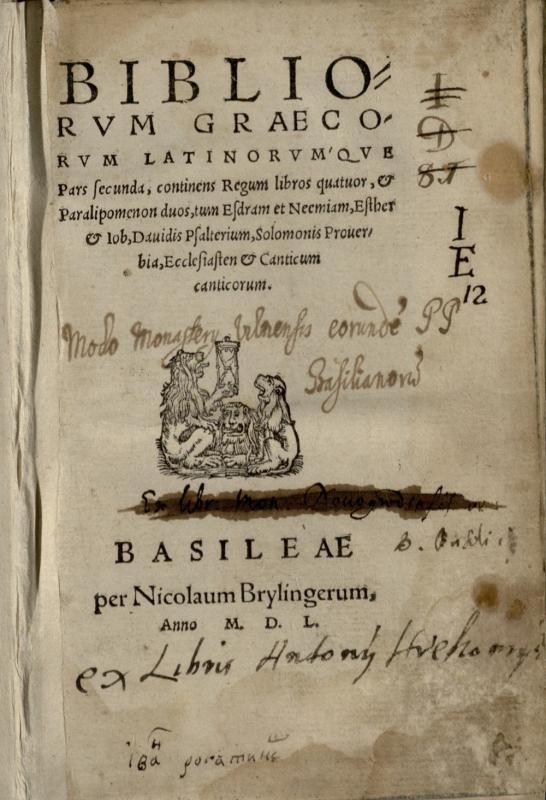

This is the second volume of the bilingual Greek-Latin Bible (the Septuagint and the Vulgate) that formerly belonged to the Vilnius Basilian Monastery.

This copy of the Latin Bible printed in Zurich used to belong to a Reformation follower and the pioneer of critical biblical exegesis in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Simeon Budny (1530–1593). The book is filled with his comments written in his hand in black and red ink. He might have used this book in the preparation of his translation of the Bible.

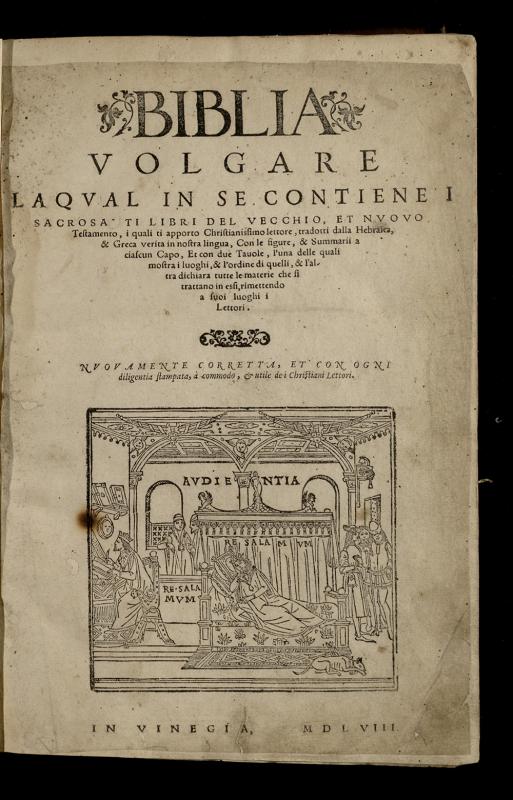

A copiously decorated translation of the Bible into Italian printed in Venice. To help the reader better understand the illustrations, some of the latter contain inscriptions naming the people portrayed. Such a caption can even be seen on the title page, decorated by an engraving with King Solomon reclining on a throne in the center. However, not all the images in the book correspond to the text, some of the engravings occurring more than once.

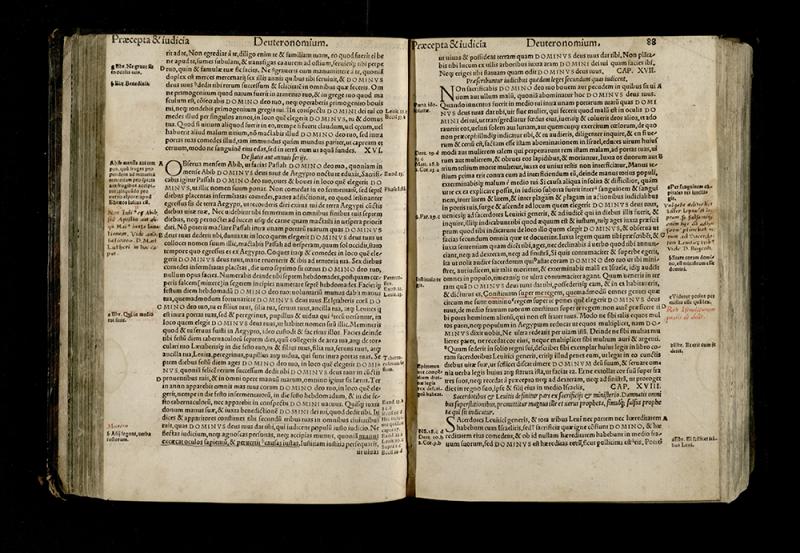

The Bible in Latin with copious commentaries printed near the text.

The main text of the Holy Scripture is printed here in a larger font, to stand out better on the page. The commentaries are printed in smaller font: the smaller the font, the less significant the commentary. The illustrations (here we see an altar for burning sacrifices) also have captions containing explanations of the meaning and the use of the objects depicted.

The Brest (Radziwiłł) Bible is the first translation of the Bible into Polish in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, prepared on the initiative of Mikalojus Radvila (Mikołaj Radziwiłł) the Black by Lithuanian and Polish Reformers. The Bible was translated from Hebrew and Greek (with the use of Latin and even French texts) into Polish by an international intellectual team headquartered in Pińczów (Lesser Poland). A total of 18 translators have been reported to participate in the effort. The translation took about six years in this Evangelical Reformed center. The published book was disseminated both locally and in the Central and Eastern Europe by the effort of the Prince himself. The Bible became known not only in the Protestant, but also in the Orthodox environment.

For more on this Bible and the context of its appearance please see the virtual exhibition “500 years of the Reformation”.

![[Turovo evangelija]. XI a. Pergamentas. Bažnyt. slavų k. [Turovo evangelija]. XI a. Pergamentas. Bažnyt. slavų k.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/e343adbdc4971691eb5f2fae57d2762e6fad9b0a.jpg)

![Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia [Paryžiaus Biblija]. Prancūzija, XIII a. Pergamentas. Lotynų k. Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia [Paryžiaus Biblija]. Prancūzija, XIII a. Pergamentas. Lotynų k.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/d2a638097c783b54713fbe649fc1e9414c7d2c47.jpg)

![Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia [Paryžiaus Biblija]. Prancūzija, XIII a. Pergamentas. Lotynų k. Sanctus Hieronimus Biblia [Paryžiaus Biblija]. Prancūzija, XIII a. Pergamentas. Lotynų k.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/80d7f1ea6b12bf5da6ee30ab5ff84fef12f72135.jpg)

![[Mažųjų Žuchavičių evangelija]. XVI a. Bažnyt. slavų k. [Mažųjų Žuchavičių evangelija]. XVI a. Bažnyt. slavų k.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/b33d384158051b6ba4b57eb558d52bbee02b9dba.jpg)

![[Nobelio evangelija]. Baltarusija, 1520. Bažnyt. slavų k. [Nobelio evangelija]. Baltarusija, 1520. Bažnyt. slavų k.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/c4a04c128950c01072dd992afce56a4f26cbee4f.jpg)

![Biblia Latina. [Venezia: Nicolaus de Francofordia, ca 1485]. Biblia Latina. [Venezia: Nicolaus de Francofordia, ca 1485].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/348701a84192a422e4be1f3966fe8a95f8da7f55.jpg)

![Biblia Latina. Venetijs: per Franciscum de Hailbrun, [1480]. Biblia Latina. Venetijs: per Franciscum de Hailbrun, [1480].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/eb23a36724225efc9426d86ece4f0b19e6a33c28.jpg)

![Biblia Bohemica. Praha: [Jan Kamp], 1488 08. Biblia Bohemica. Praha: [Jan Kamp], 1488 08.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/222407dfe8344c75eedc05668d059422c7d297ee.jpg)

![Бивлия Руска: Книги четвертые Моисеевы, зовемые Числа. Прага, [1519]. Бивлия Руска: Книги четвертые Моисеевы, зовемые Числа. Прага, [1519].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/f70b215077eb147d47f92ed9dde0761ee2c77c99.jpg)

![Бивлия Руска: Книги четвертые Моисеевы, зовемые Числа. Прага, [1519]. Бивлия Руска: Книги четвертые Моисеевы, зовемые Числа. Прага, [1519].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/c2004eb40b359c23bab47233a9e8f4fd76a6c39d.jpg)

![Biblia utriusque Testamenti, de quorum nova interpretatione et copiosissimis in ea mannotationibus lege quam in limine operis habes epistolam. T. 1. [Genevae]: oliva Roberti Stephani, 1556–1557. Biblia utriusque Testamenti, de quorum nova interpretatione et copiosissimis in ea mannotationibus lege quam in limine operis habes epistolam. T. 1. [Genevae]: oliva Roberti Stephani, 1556–1557.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/01a026fab8634b0b206b702184e0db9cb5a0c5a9.jpg)

![Biblia utriusque Testamenti, de quorum nova interpretatione et copiosissimis in ea mannotationibus lege quam in limine operis habes epistolam. T. 1. [Genevae]: oliva Roberti Stephani, 1556–1557. Biblia utriusque Testamenti, de quorum nova interpretatione et copiosissimis in ea mannotationibus lege quam in limine operis habes epistolam. T. 1. [Genevae]: oliva Roberti Stephani, 1556–1557.](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/793de0c4a3444a03b476148f765fea7a93dd3c1f.jpg)