Beginning of the Printing

Incunabula as a Continuation of the Manuscript Tradition

In 15th-century Europe, all the conditions for the emergence and spread of printing in typeset characters had been met. Already in the 14th century, woodcuts were used to print on cloth. The Italian artist Cennino d'Andrea Cennini (c. 1360 - before 1427), in his famous work “Il libro dell'arte”, described how to make stamps out of walnut, pear or other hard woods that could be used to decorate linen, which would then be used to make children's clothes. Adults’ clothes were made from more expensive fabrics, where patterns had already been woven in.

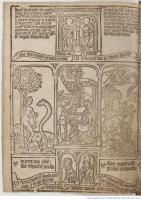

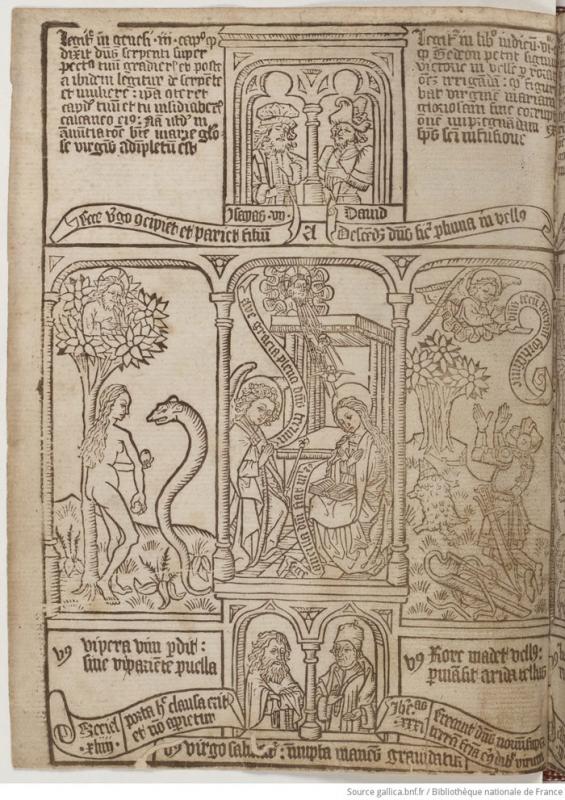

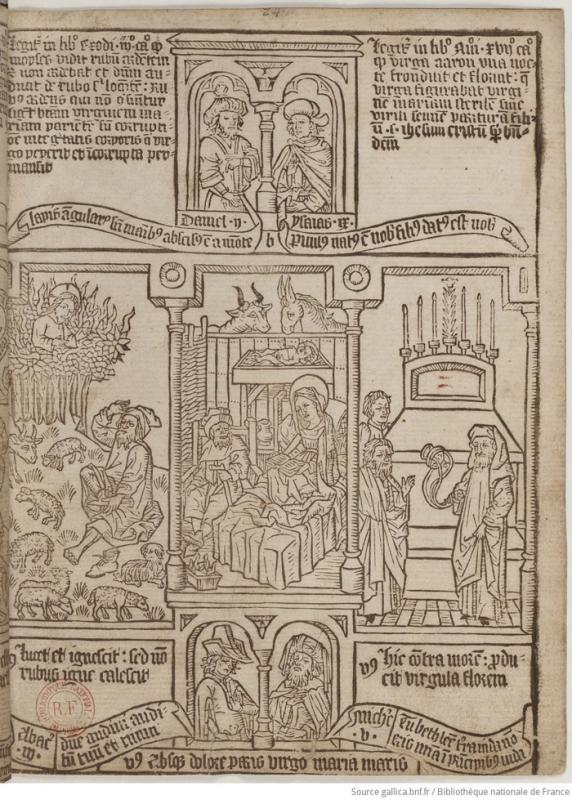

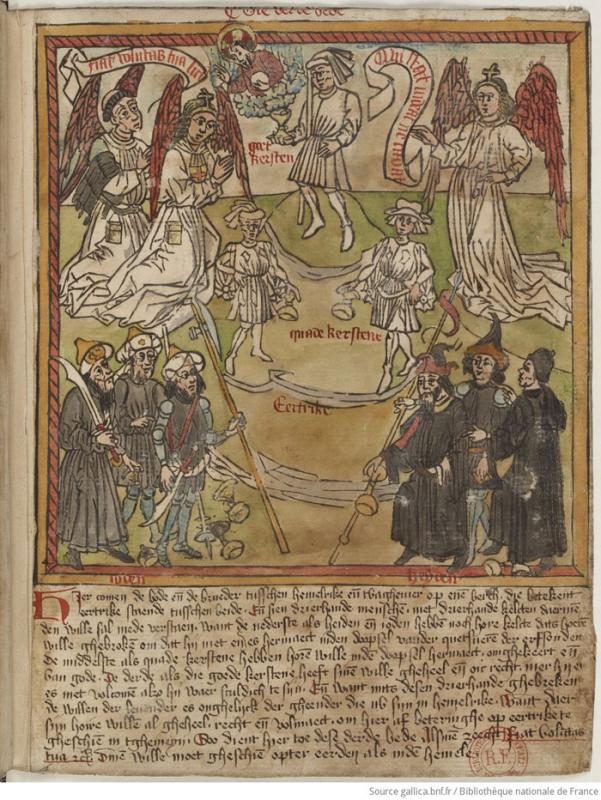

In the 15th century, wood and copper engravings were used to produce more than just drawings. By cutting letters alongside pictures, it was possible to print the whole page and thus – using the so-called xylography – produce the desired number of books more quickly.

BnF, RLR, Xylo-4

gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

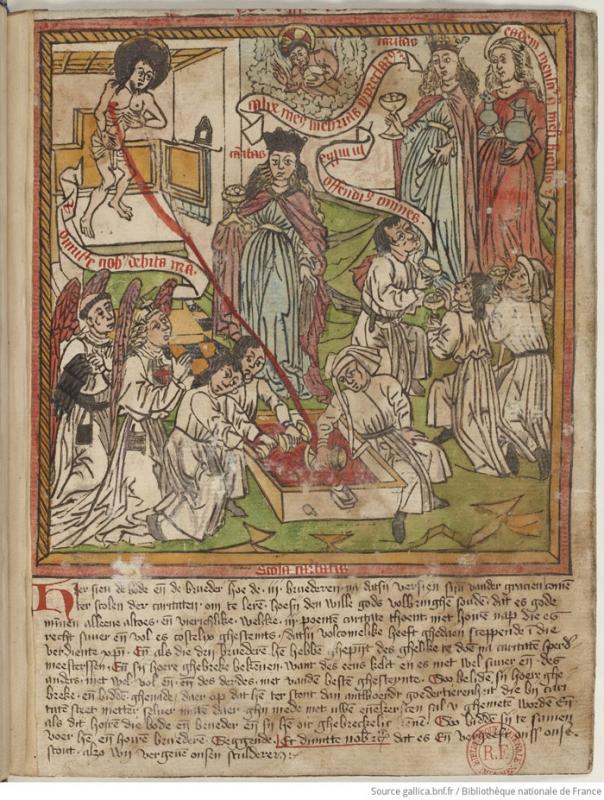

In addition to these engraved books, semi-printed (chiro-xylographic) books were also produced. Here the drawings were stamped and the text handwritten.

BnF, RLR, Xylo-31

gallica.bnf.fr / Bibliothèque nationale de France

Another important factor for the spread of printing was that by the second half of the 15th century there were already many paper mills in Western Europe and the production of this less expensive and more accessible writing material had been perfected. European parchment manufacturers could not have found the number of cattle and prepared the quantity of skins needed to meet the ever-increasing demands of printers.

But perhaps the most important reason was the growth of literate people and the expansion of the book trade. A manuscript preserved in the library of the University of Leiden (the Netherlands) testifies the circulation of manuscript books in the first half of the 15th century. The text, dated 1437, is a commission for a scriptorium master; a request for 200 copies of the seven penitential psalms, 200 copies of the Cato’s distichs in Flemish and 400 copies of small prayer books. At the time, book fairs were no longer a novelty either. It is known that books were traded at Frankfurt fairs since the 12th century.

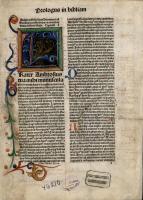

The history of printed books is usually traced back to Johannes Gutenberg's printing of the 42-line Bible. The book was completed in 1455-1456. The 42-line Bible was named so because of the number of lines of text per page. It is worth mentioning that a few pages (the introduction by St Jerome and the beginning of Genesis, and one page of I Kings), each contains only 40 lines. In addition, they are the only pages printed in two colours: the text in black ink, the rubrics in red. On the other pages, where the publisher managed to fit in 42 lines, the space for rubrics was left blank and later filled in manually.

It is not known exactly how many copies of this book were printed: allegedly 158 or 180 copies. Almost the entire edition was printed on paper, except for about 30 of the more luxurious copies, which were printed on parchment, following the tradition of manuscript Bibles. Scholars have calculated that a single Bible printed on parchment might have required the skins of 170 calves and that 100 books would have required a herd of about 15 000 cattle. These figures explain why it was not enough to just start printing in movable-type printing press characters. It was necessary to perfect the production of paper so that a large number of books could be produced in a short time.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 2 Inc.s.a. 197-1

ISTC ib00526000, GW 04201

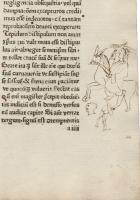

However, the oldest book printed by Johannes Gutenberg is a German political religious pamphlet "Eyn manũg d' cristẽheit widd' die durkẽ" (English: “Warning to the Christians about the Turks”), dated December 1454, between the 6th and the 24th. It addresses European rulers, who are urged to defend Christianity after the conquest of Constantinople by Turkish forces led by Sultan Mehmed II on 29 May 1453. The publication also includes a calendar for 1455 and a prayer asking for help in the fight against the Turks. The date of the publication is not known, but it can be estimated with some accuracy. The text for December concludes with information from Rome about the success of the war in Turkey. It is known that this news reached Frankfurt on the 6 December 1454. The work concludes with a greeting for the New Year of 1455, which, according to the calendar of the time in Mainz, began on the first day of Christmas. It is these two dates that allow the calendar to be dated to within a few weeks of its publication.

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Rar. 1

ISTC it00503500, GW M19909

![Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455]. Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/2a757b55aa472c68bd7b63a3653dd8c5e2e477ae.jpg)

![Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455]. Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/4772b71ea57356be07da56d1cec5ff2c11990a93.jpg)

![Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455]. Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/720238ba804ce71719ff8af1540c377ca21223df.jpg)

![Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455]. Biblia Latina. [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, Johannes Fust, ca 1455].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/9d48baed41c5d8acc6078cfc0edc1e83cf2a72d5.jpg)

![Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24]. Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/38c64192613c89b0f3b18e2725ad2a4714b787b4.jpg)

![Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24]. Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/51615a768fb0ce71cde9e36fda4e675955b61f0a.jpg)

![Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24]. Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/a65c61a9877c90e63e55fb1108bb6df5053f015f.jpg)

![Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24]. Türken-Kalender (Eyn Manung der Christenheit Widder die Durken). [Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg, 1454 12 6–24].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/61c170ef8fc2f4b1f35a41e627d084130a5ae51f.jpg)