Infancy of the Printed Book

Incunabula as a Continuation of the Manuscript Tradition

The first printed books were not called incunabula until the 17th century. This name emphasizes the “immaturity” of the first books, the “imperfection” of their form, and the fact that the more usual appearance of a book had not yet been established (Lat. “incunabula” – diaper, cradle), and that, although “written” in a new way, they still followed the tradition of manuscript books. It is agreed to use this term for all the books printed in movable-type from the beginning of such printing until the end of the 15th century, on 31 December 1500.

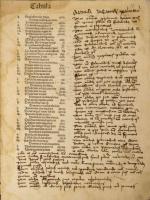

There are several features that make these books, or at least some of them, still resemble manuscripts in form. Firstly, the lack of a usual title page. These books may begin with a sentence describing the first part of the book, the first chapter, or in any other manner discuss the following text.

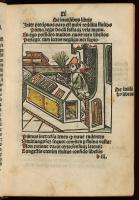

In one incunabulum, the former owner of the book wrote that it is the book of the Augustinian Father Jacobus Philippus, "Supplementu[m] chronicaru[m]". At the beginning of the text on the first page, without this handwritten commentary, the reader would only observe a table of the following printed chronicles: an alphabetical list of names, places and things, with references to where they are to be mentioned in the text. However, the reader would fail to find information about the author or anything related to publication.

LMAVB RSS I-32

ISTC ij00211000, GW 14129

The first sentence of a book's text sometimes indicates the author and title of the work, but usually this information is written in a descriptive style. In the case presented here, st. Eusebius' letter about st. Jerome's death is not mentioned as it is. Instead, a brief description of both the author and st. Jerome is given, which also indicates thatthat the following letter concerns the saint’s death.

LMAVB RSS I-12c

ISTC ih00244000, GW 09453

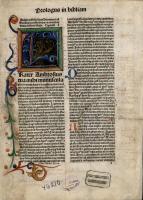

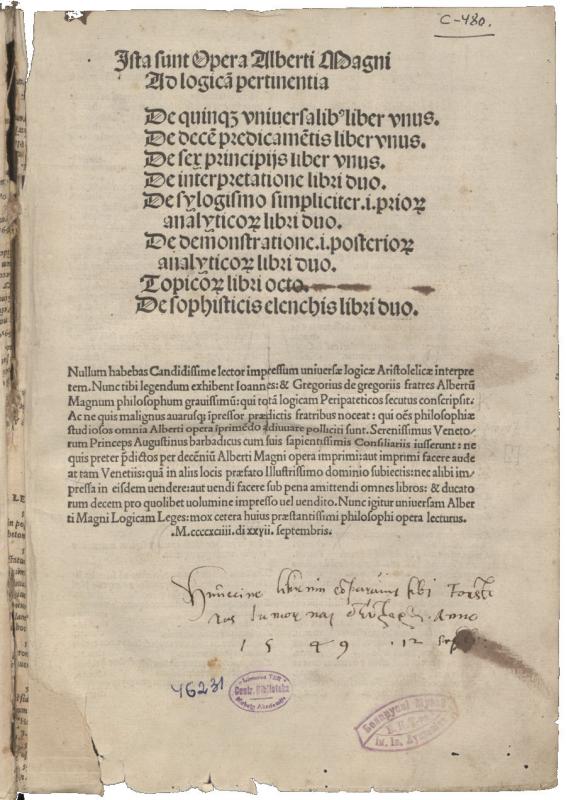

The title and author of the work, written on the first page, can be seen as the early attempts to create what will later become the title page.

LMAVB RSS I-12b

ISTC ia00310000, GW 00731

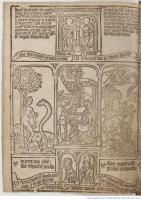

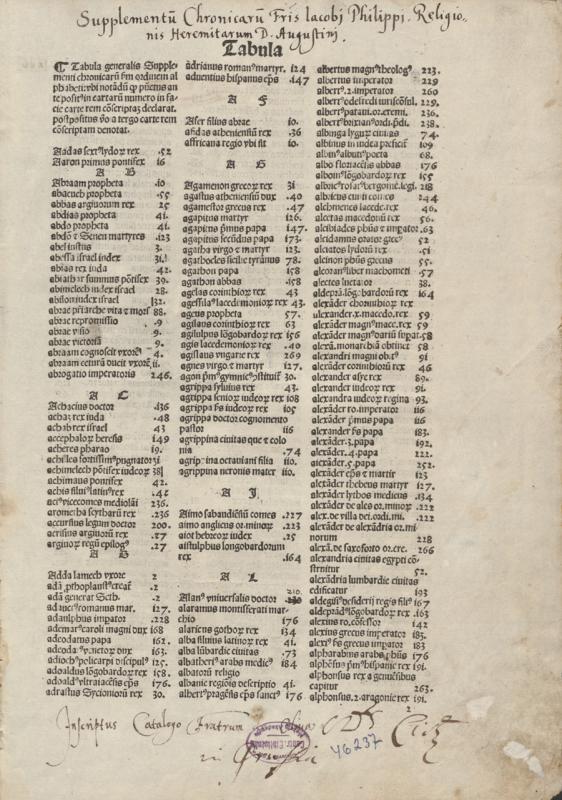

In the more sumptuous, illustrated works the title could be incorporated into the engraving that decorated the first page.

LMAVB RSS I-16

ISTC ic00488000, GW 04963

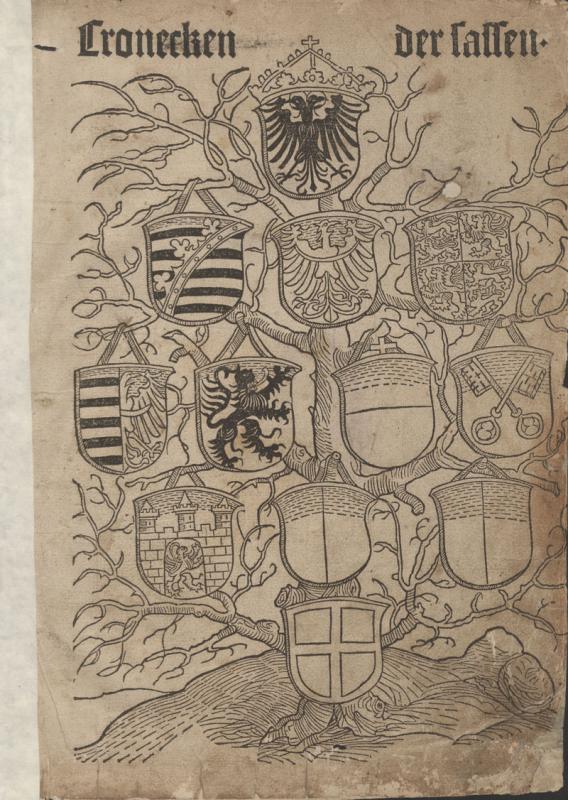

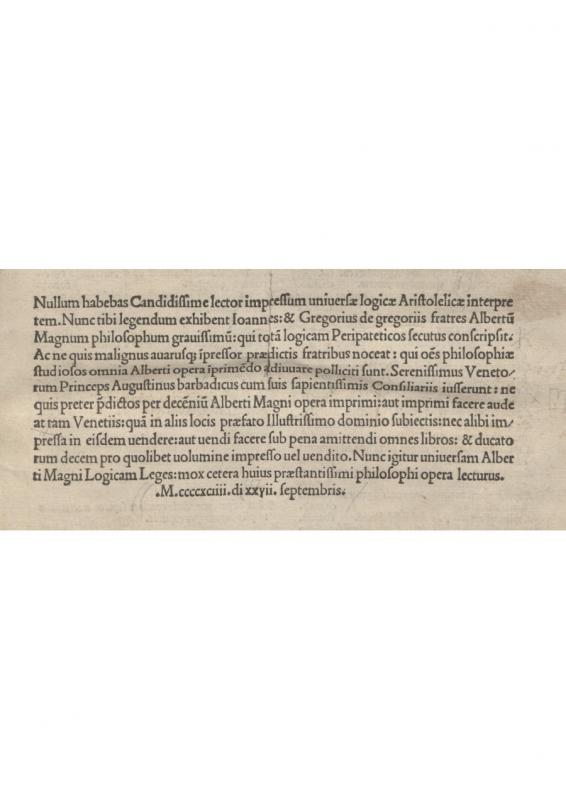

Sometimes even more information is added to the first page, the future title page. On the first page of Albert the Great's Logic, one can read not only which works make up the book, but also a kind of advertisement – an address from the printers to the reader, describing both the importance of the work and simultaneously praising the physical book itself. This text contains both the publishers named in the third person and the date on which the text was published.

LMAVB RSS I-26a

ISTC ia00270000, GW 00677

As can be seen from the examples above, the information printed at the beginning of the book varies: sometimes one finds very little of it; sometimes none at all. Here, the printers were still following the medieval book tradition, where a title page often did not exist.

The basic information about the work – author, title, printer, place and date of publication –is not printed at the beginning of the work, but at the end of the book, in a loose descriptive form in one or more sentences, a so-called colophon. This colophon part never became commonplace, therefore the amount of information can vary, with sometimes none given at all.

Nicolaus Keßler, the printer of Basel, not only indicates the title of the book (Regimen sanitatis) and its author (Magninus Mediolanensis) in the colophon, but also expresses his satisfaction that the work had been completed successfully.

LMAVB RSS I-12a

ISTC im00054000, GW M19890

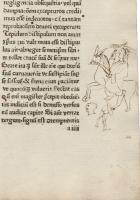

At the beginning of Albert the "Great's Secreta mulierum et virorum", there is no information supplied about the publisher. At the end, the reader may find only the laconic phrase "Laus Deo" (Glory to God). However, this is still more than in some other incunabula, where the book has only the beginning and end of a text with no sign of the publisher at all.

LMAVB RSS I-12b

ISTC ia00310000, GW 00731

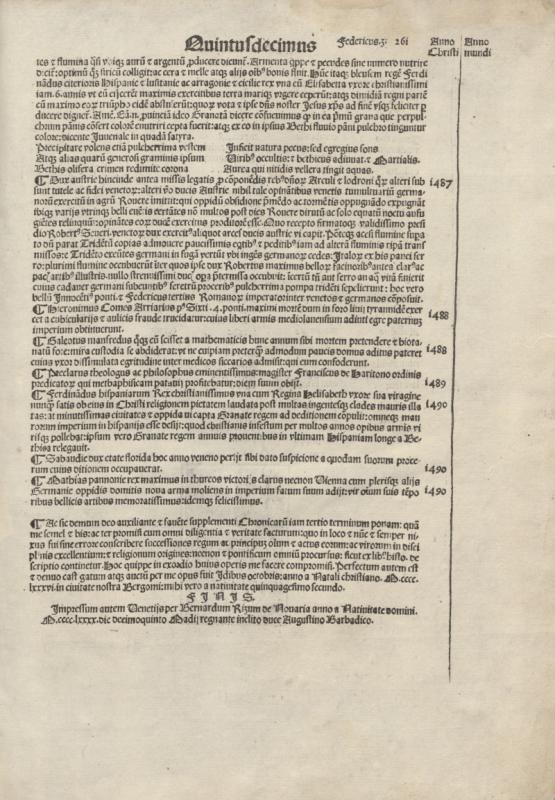

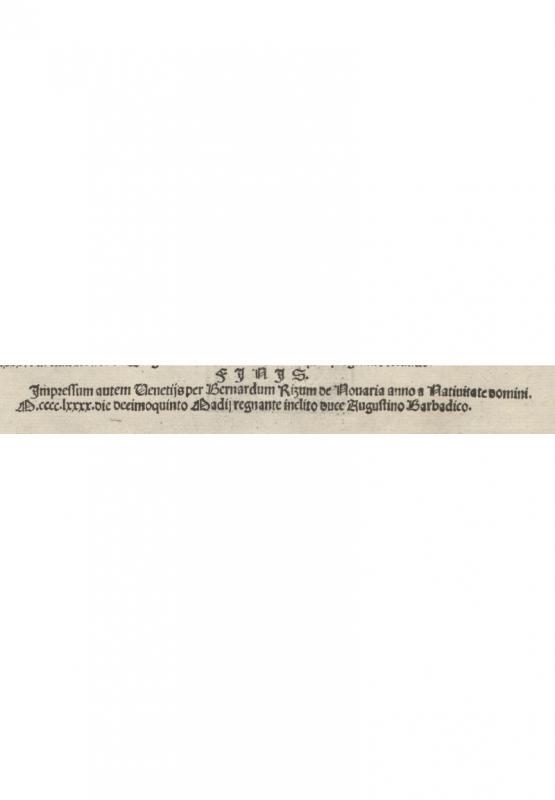

The description of the year may vary as well. The usual "anno Domini" (the year of the Lord) is often replaced with various other expressions that have the same or similar meaning: "anno a Nativitate Domini" (from the Lord's birth; this means that the year begins on 25 December instead of 1 January), "anno humane salutis" (the year of human salvation), or simply "anno salutis" (the year of salvation). Other events or persons may also be referred to when the year is specified. The Venetian printer Bernardinus Rizus, for example, indicates that at the time of the printing of the book Venice was ruled by Duke Augustinus Bardaricus.

LMAVB RSS I-32

ISTC ij00211000, GW 14129

Another book reveals the fact that the document was written and printed in the third year of the papacy of Pope Alexander VI.

LMAVB RSS I-12j

ISTC ia00379250, GW 00918

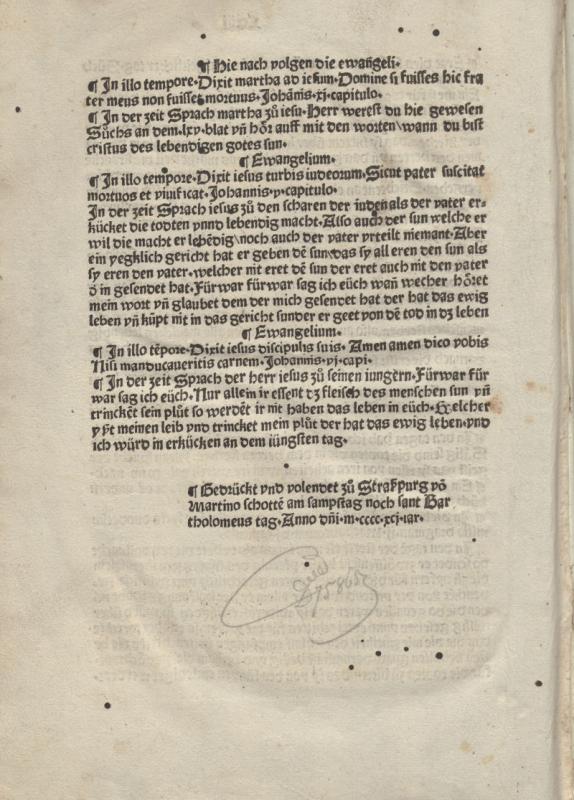

Methods of recording the exact date have also varied. In the 15th century it was common to mention liturgical feasts instead of the month and the day. One such example is the Gospels and the Epistles with Glosses, printed on the Saturday after the feast of St. Bartholomew. This Saturday of that year was 27 August.

LMAVB RSS I-15

ISTC ie00084780, GW M34139

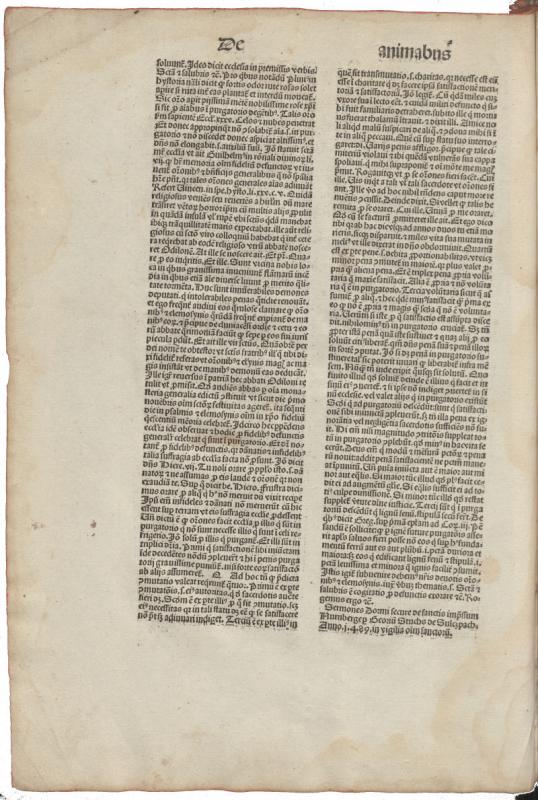

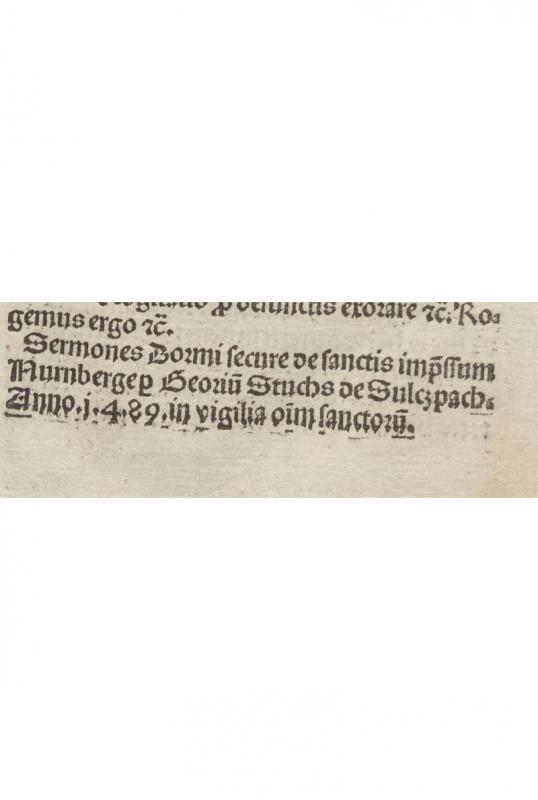

This method of dating is important not only because it gives a very clear picture of how time was counted in the 15th century, but also because it shows that the supposedly exact date in the book is not necessarily correct. There are incunabula which contain statement that they were printed on church festivals, such as the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (15th of August), or Christmas – the feast of the birth of Jesus Christ. Of course, the printers were not working those days, so either they hoped to finish the work by that day, or they were dedicating the book to a soon-to-be or recently celebrated feast. It is likely that the other dates given may not have been entirely accurate either. After all, even if by an incredible coincidence the Nuremberg printer Georgius Stuchs really managed to complete the printing of Johannes de Werden's collection of sermons “Sermones "Dormi secure" de sanctis” by the eve of All Saints’ Day, "in vigilia o[mn]i[u]m sanctoru[m]", it does not retract from the fact that the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary or Christmas Day were celebrated by the 15th century printers.

LMAVB RSS I-27

ISTC ij00462500, GW M14948

![Pseudo-Eusebius Cremonensis. Epistola de morte Hieronymi etc. [Antwerpen: typ. Mensa philosophica, ca. 1487 04 07]. Pseudo-Eusebius Cremonensis. Epistola de morte Hieronymi etc. [Antwerpen: typ. Mensa philosophica, ca. 1487 04 07].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/353780ab469338aa4e381607a9f3e5a59bc1bd4b.jpg)

![Albertus Magnus. Secreta mulierum et virorum. [Leipzig: Conrad Kachelofen, ca 1492]. Albertus Magnus. Secreta mulierum et virorum. [Leipzig: Conrad Kachelofen, ca 1492].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/aadd7eedfc4da8bdee456c09595eb39e78561f41.jpg)

![Magninus Mediolanensis. Regimen sanitatis. Basel: Nicolaus Kesler, [non ante 1493 11 08]. Magninus Mediolanensis. Regimen sanitatis. Basel: Nicolaus Kesler, [non ante 1493 11 08].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/19fd86b4aba2ad25cf773616a2473fa35f62cd8e.jpg)

![Magninus Mediolanensis. Regimen sanitatis. Basel: Nicolaus Kesler, [non ante 1493 11 08]. Magninus Mediolanensis. Regimen sanitatis. Basel: Nicolaus Kesler, [non ante 1493 11 08].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/0bef3ffc81724e1ee0ffcff5c332b26a6bd618d6.jpg)

![Albertus Magnus. Secreta mulierum et virorum: (cum commento). [Leipzig: Conrad Kachelofen, ca 1492]. Albertus Magnus. Secreta mulierum et virorum: (cum commento). [Leipzig: Conrad Kachelofen, ca 1492].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/68e5f1e51cb7369d8fe7bf8a2b40e4d6e8ea6835.jpg)

![Albertus Magnus. Secreta mulierum et virorum: (cum commento). [Leipzig: Conrad Kachelofen, ca 1492]. Albertus Magnus. Secreta mulierum et virorum: (cum commento). [Leipzig: Conrad Kachelofen, ca 1492].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/24ff2369e4f43889324dee3d68c95785b34ceba4.jpg)

![Alexander VI. Regulae cancellariae, 8 Aug. 1495. [Roma: Stephan Plannck, non ante 1495 08 08]. Alexander VI. Regulae cancellariae, 8 Aug. 1495. [Roma: Stephan Plannck, non ante 1495 08 08].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/00c739664e44ab2afdb035e9ff36d76de70c2647.jpg)

![Alexander VI. Regulae cancellariae, 8 Aug. 1495. [Roma: Stephan Plannck, non ante 1495 08 08]. Alexander VI. Regulae cancellariae, 8 Aug. 1495. [Roma: Stephan Plannck, non ante 1495 08 08].](http://web6.mab.lt/files/large/36c5c6e887f4a1b61db2c2ae1a9baa7305ef137e.jpg)