Preface

In October 1454, the Italian humanist Enea Silvio Piccolomini (1405-1464) – the future Pope Pius II – was visiting Frankfurt when he met an unknown “vir mirabilis”, an extraordinary man (it is not known whether it was Johannes Gutenberg himself or one of his assistants). Recounting this encounter in a letter of 12 March 1455 to Cardinal Juan Carvajal (c. 1400-1469), Piccolomini said that he had seen a dozen pages from 158 or even 180 identical copies of the Bible, which could be read without spectacles, and marvelled at the speed with which the book had been produced.

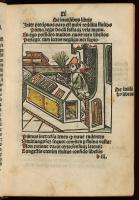

What amazed Piccolomini was the appearance of one of the first incunabula, Gutenberg's 42-verse Bible. Although Enea Silvio Piccolomini realised that he was witnessing an enormous advance, neither he nor Gutenberg himself could have imagined at the time what this invention would become. At that time, even 180 Bibles seemed a huge number compared to the work of the manuscript writers. Although printing with wooden blocks began in China no later than the 9th century, and metal typesetting was introduced in Korea in the 14th century, it was in Europe that printing revolutionised book production. The symbol of this process became the Gutenberg Bible, which was printed in Mainz in 1455. In the five decades of the 15th century millions of books were published and spread throughout Europe, of which around half a million have survived to the present day.

More than half a thousand incunabula are currently counted in Lithuania and this number is slowly but surely increasing. The Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences currently holds 67 incunabula (one of which was identified during the preparation of the exhibition). This exhibition aims to present the incunabula, their unique features, and to show how the form of the first printed documents has evolved, allowing the book gradually to become what we are used to seeing nowadays. The visitors are also invited to become acquainted with the incunabula of the Wróblewski Library, to see their curiosities, and the uniqueness of individual specimens in one way or another. However, the exhibition does not pretend to be objective, especially in regard to that which is beautiful or interesting. The audience is invited to follow the links to view the books that were discussed in this exhibition or only mentioned in the Wroblewski Library's list of incunabula, and to discover which ones are of personal interest. As the digitisation of the Wroblewski Library's incunabula is completed, those who want to get to know one or another book in detail can browse the document of interest online. The links to the incunabula will be updated after the books have been digitised.

All the incunabula in the virtual exhibition are described mainly using the British Library's Incunabula Short Title Catalogue, which, together with the German catalogue of incunabula, Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke (GW), are the primary sources for researchers. Source numbers, which are given alongside the book descriptions, are the modern identification code for these books.

Exhibition designer and writer: Agnė Zemkajutė

English editor: Saulius Venclovas

Posted online: Audronė Steponaitienė