How the Printed Text was Adorned

Incunabula as a Continuation of the Manuscript Tradition: A Good Start is Only Half of the Work

Both the copying of the book and its publishing were only the first stage of the process of the text becoming a book. The scribe's work – the book to be – was quite often still adorned by the illuminator, the artist of the miniatures that still fascinate us today. Printed books could also be decorated: a person who had the money and could afford to buy a more sumptuously decorated book would take it to an artist.

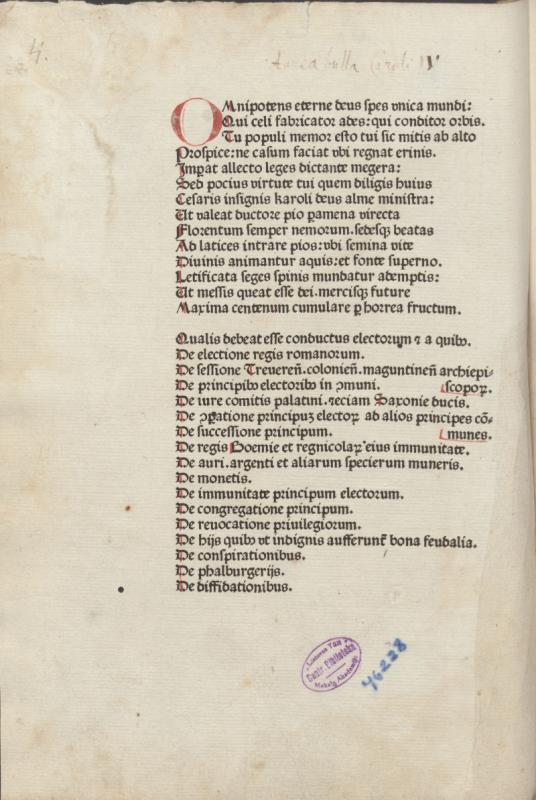

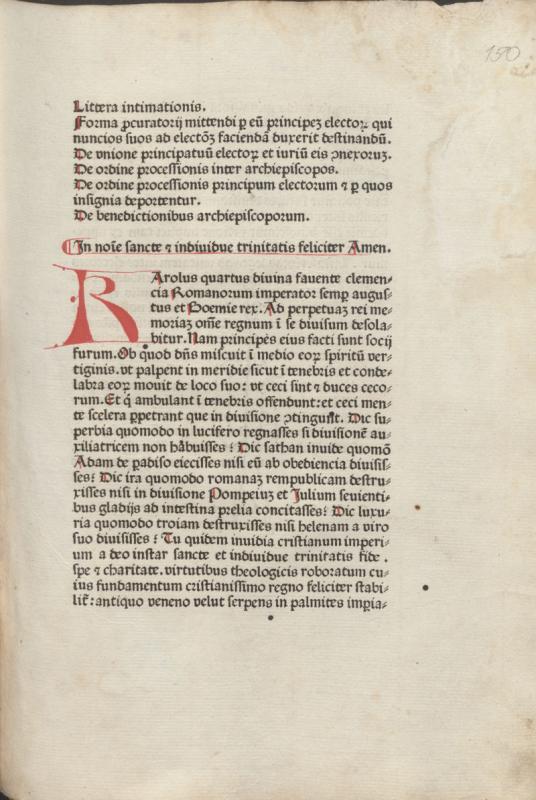

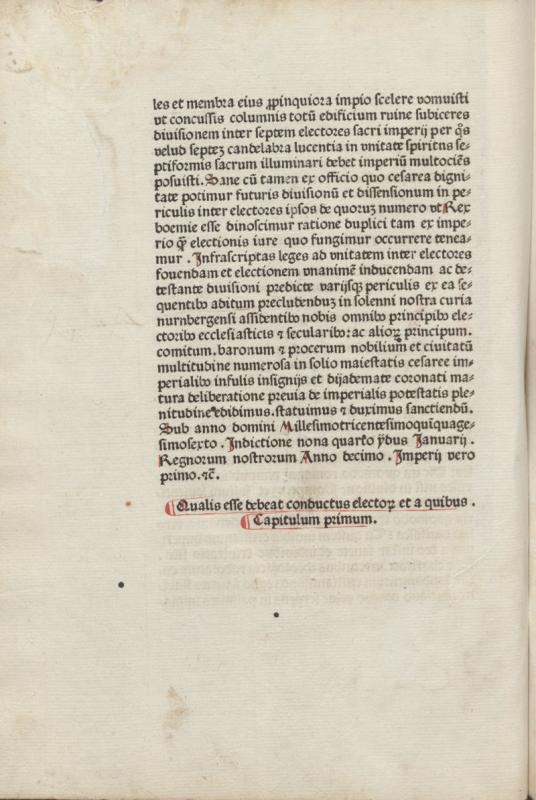

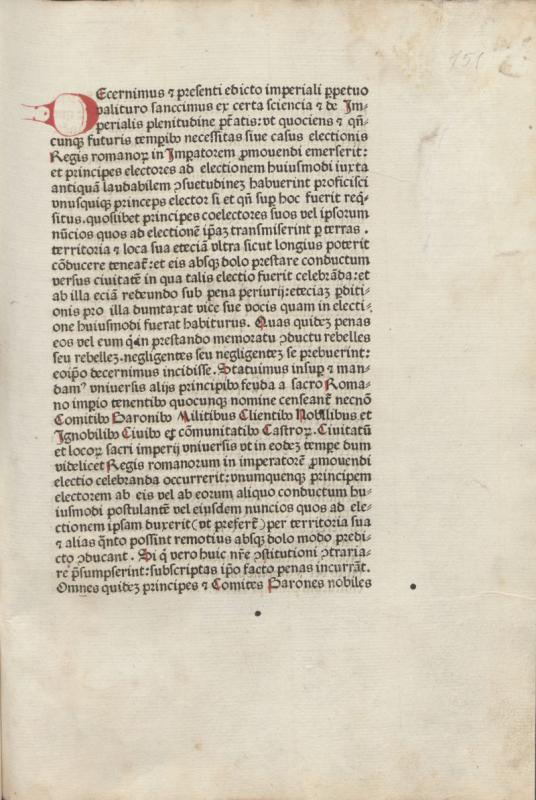

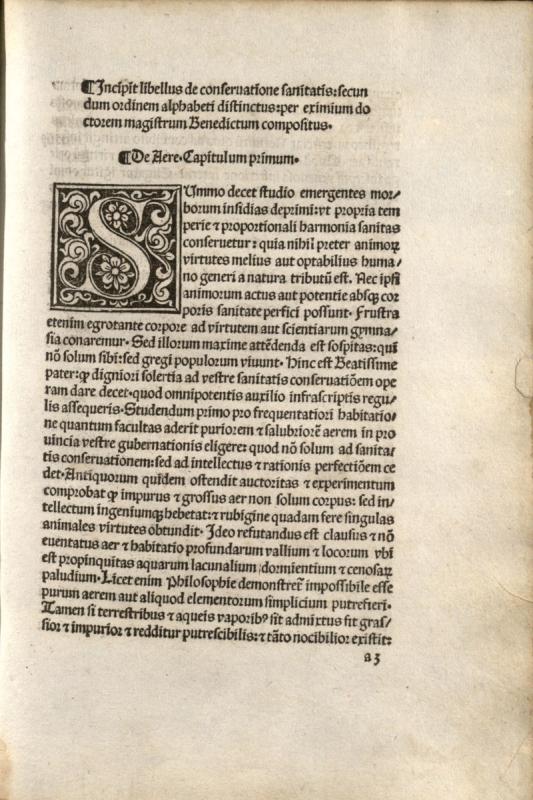

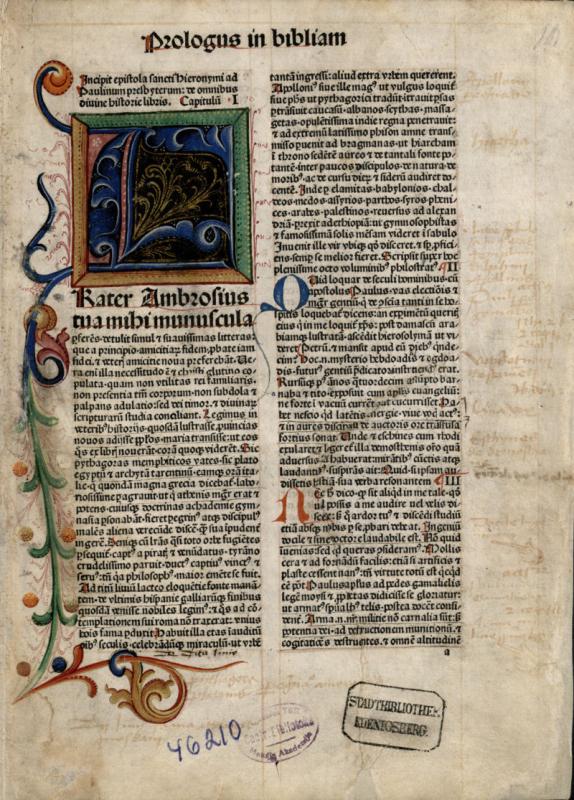

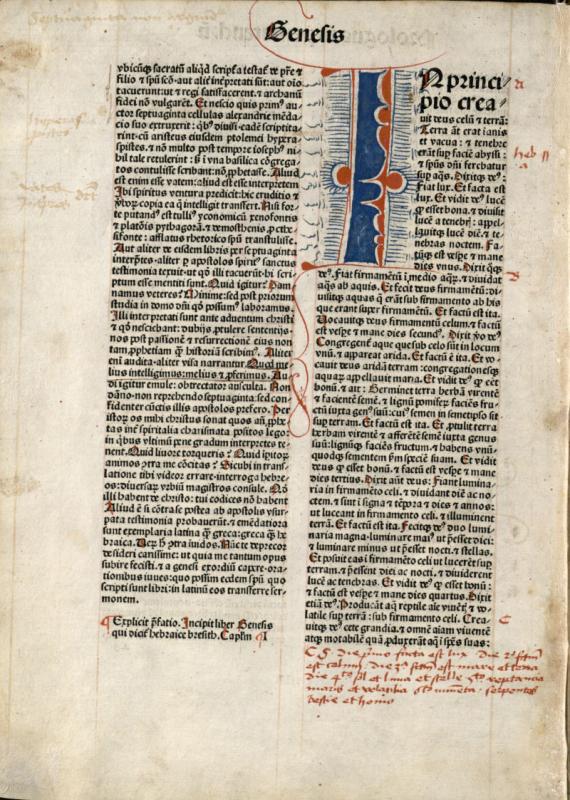

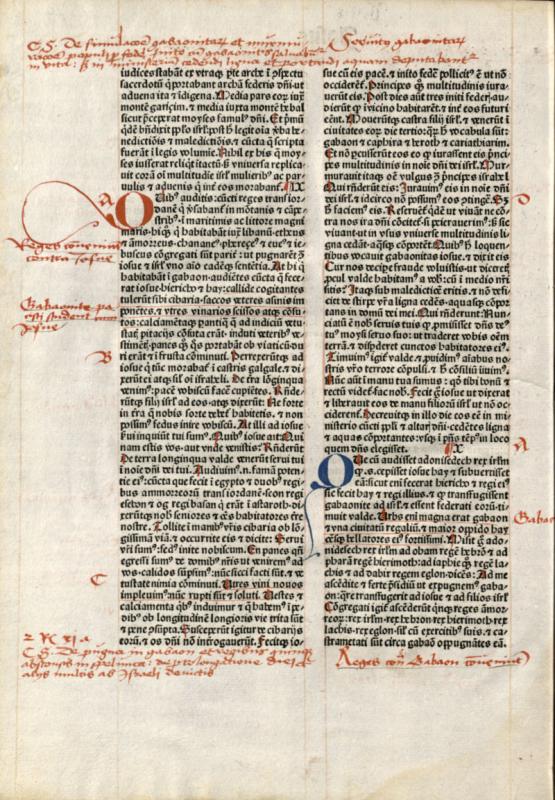

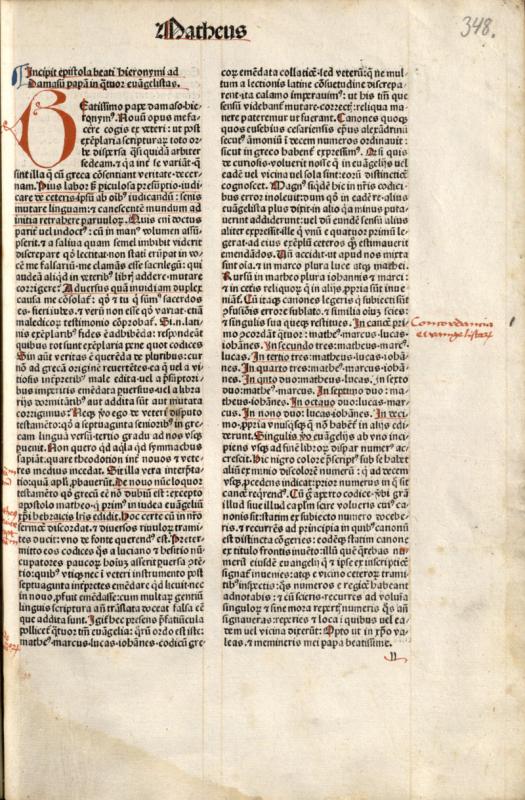

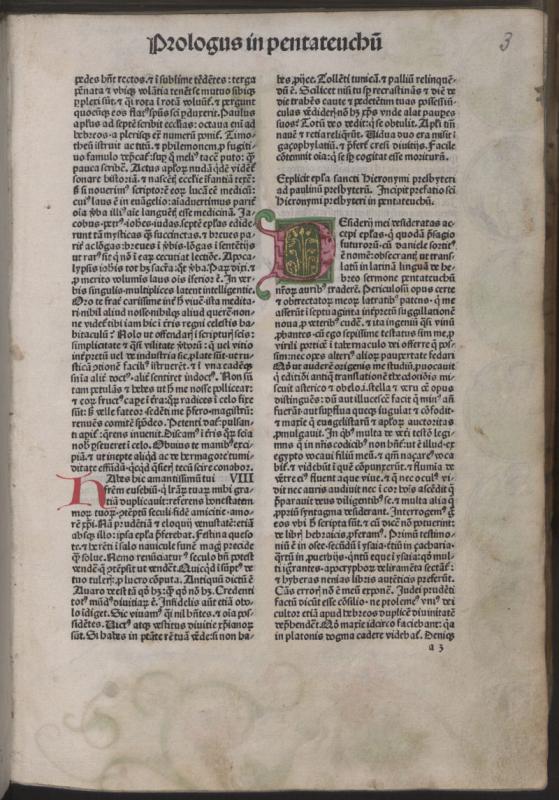

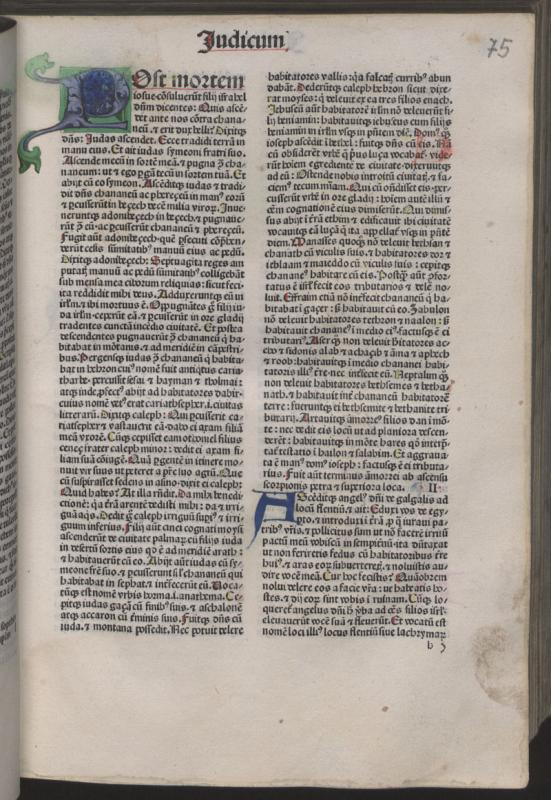

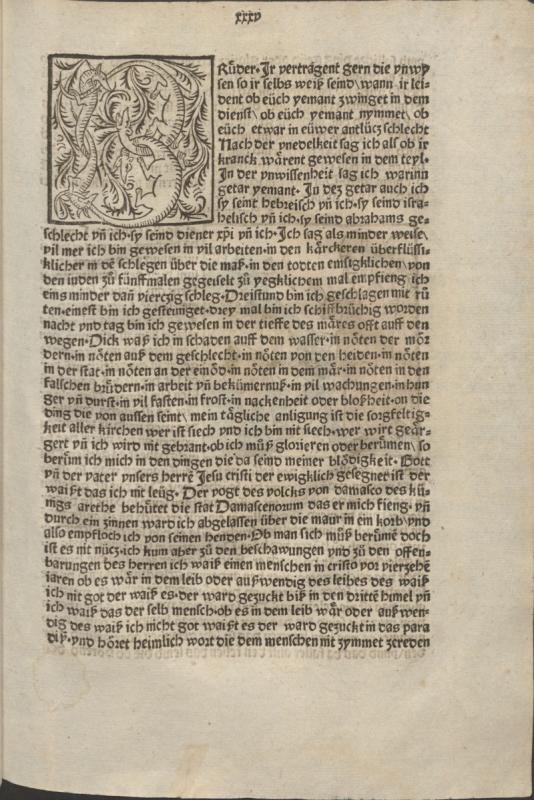

In incunabula, the text was usually poorly structured, with few or no clearly visible paragraphs, often divided only into chapters. It was difficult to read such a long, singular text. The first letters of sentences, the rubrics (Latin ruber – red), were marked in red ink by an artist called rubricator to make thereading easier. Unless the book was highly ornate, the rubricator would inscribe the first letters of the chapters, for which the printer would also leave more space, often stamping a small letter, known as the 'waiting letter', to help the artist avoid making a mistake. Such letters were also included in manuscripts, but we do not usually see them, as they are covered by a more ornate or simpler miniature.

Since it cost money to mark each heading and draw each miniature, it was up to the buyer of the book to decide how it would be bound and whether it would be taken to the rubricator. Today we can see not only how differently books were decorated, but also how the text looked once it was printed. Obviously, the text was important to the owner of the book: a large work would have had to cost a lot, even without additional decorations.

LMAVB RSS I-26b

ISTC ia00222000, GW 00586

Where rubrics were marked, they divided the text and made it easier to read.

LMAVB RSS I-25e

ISTC ic00206000, GW M16087

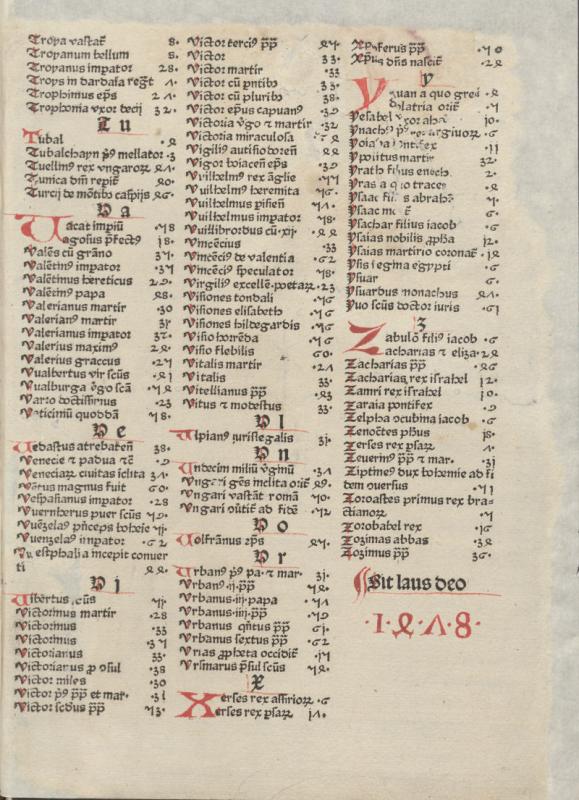

Most of the time rubricators remained unknown, as they left no personal marks in the books. However, there are exceptions. In Werner Rolewinck's Fasciculus temporum, at the end of the index, under the printed text “Sit laus Deo” (Glory be to God), the year “1478” is written in red ink, the same ink that was used for the rubric. It can be assumed that the rubricator, having completed his work, wrote the year. Doing this he continued the thought of the publisher and joined his desire to glorify God through his work.

LMAVB RSS I-25a

ISTC ir00257000, GW M38715

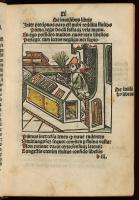

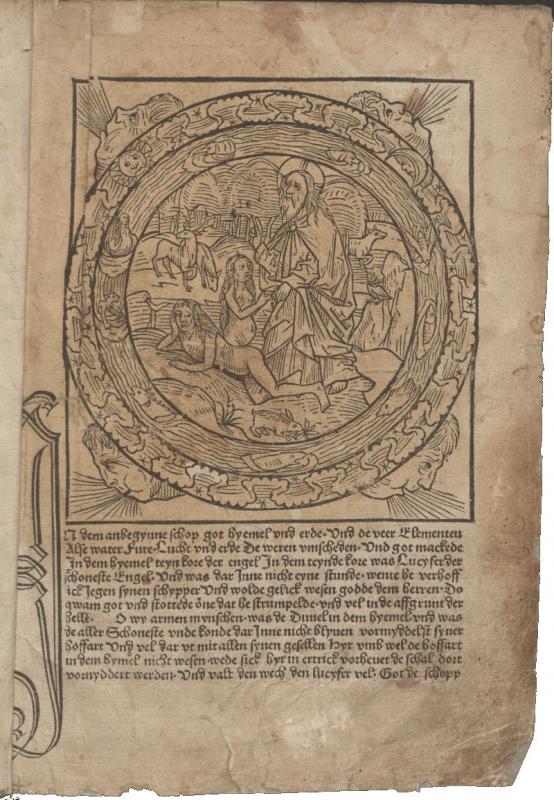

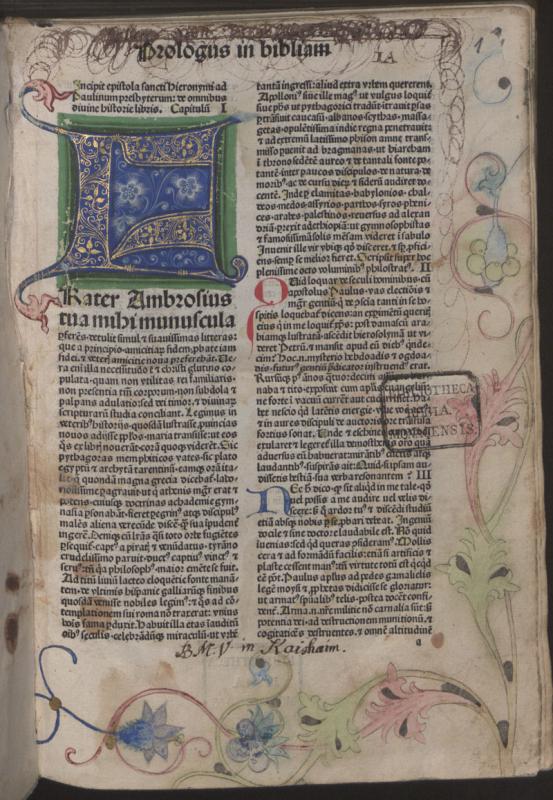

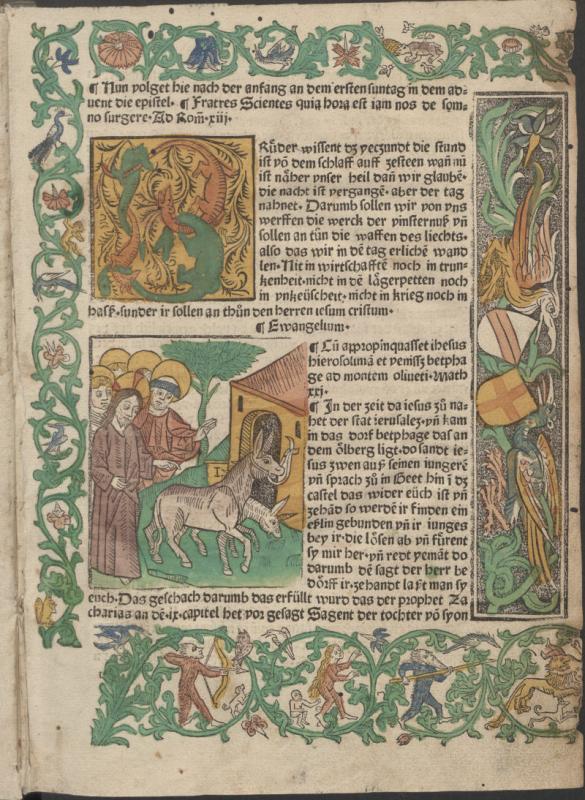

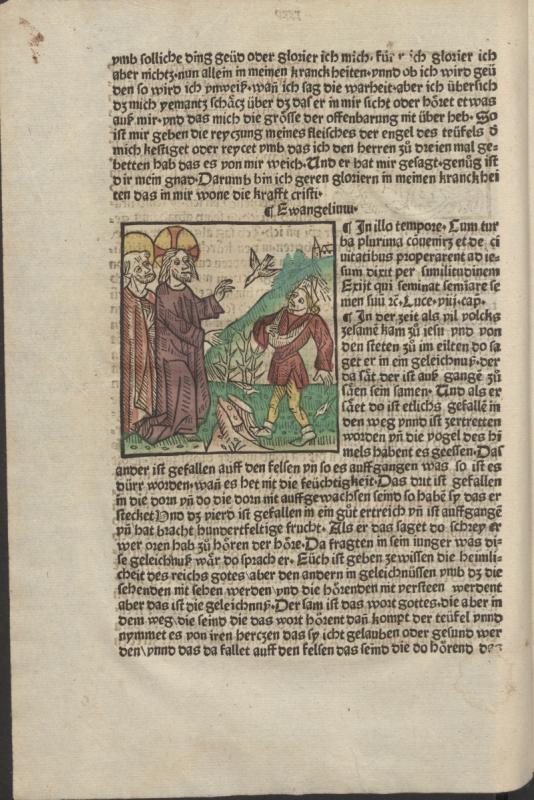

Printing also made it possible to at least partially cheapen the decoration of the book. Illustrations or entire books were already being printed, with the entire page carved on a single wood panel. Incunabula printers also made use of engravings. They offered books in which more ornate letters decorated the beginnings of chapters.

LMAVB RSS I-12d

ISTC ib00319000, GW 03824

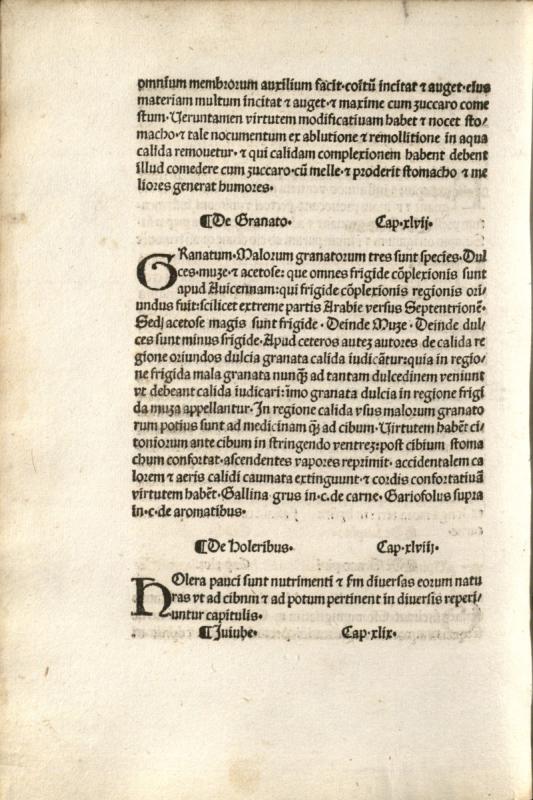

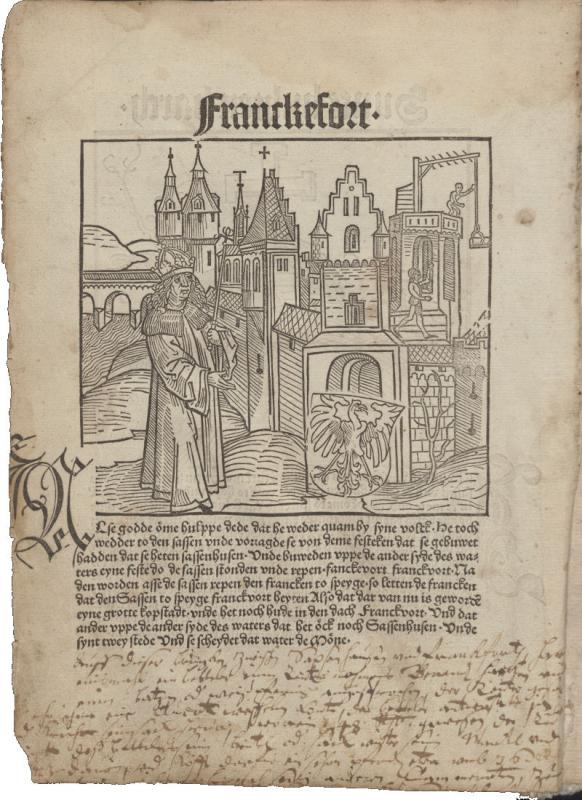

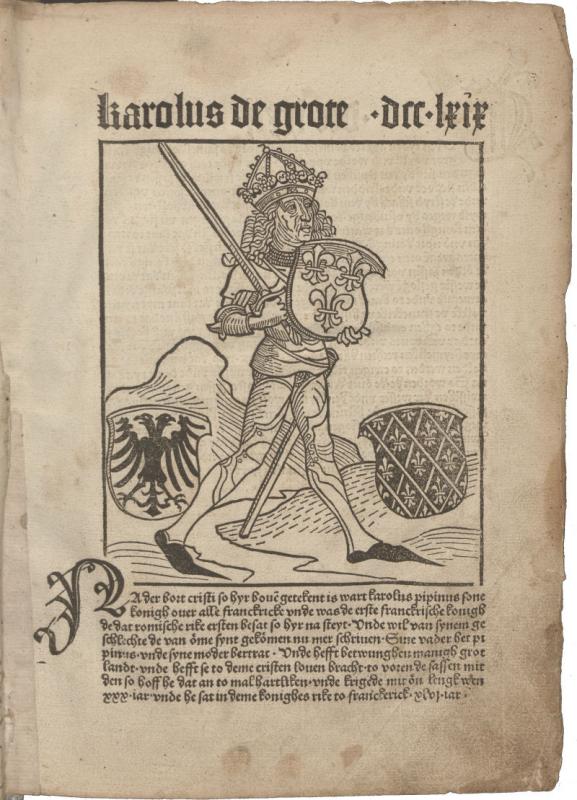

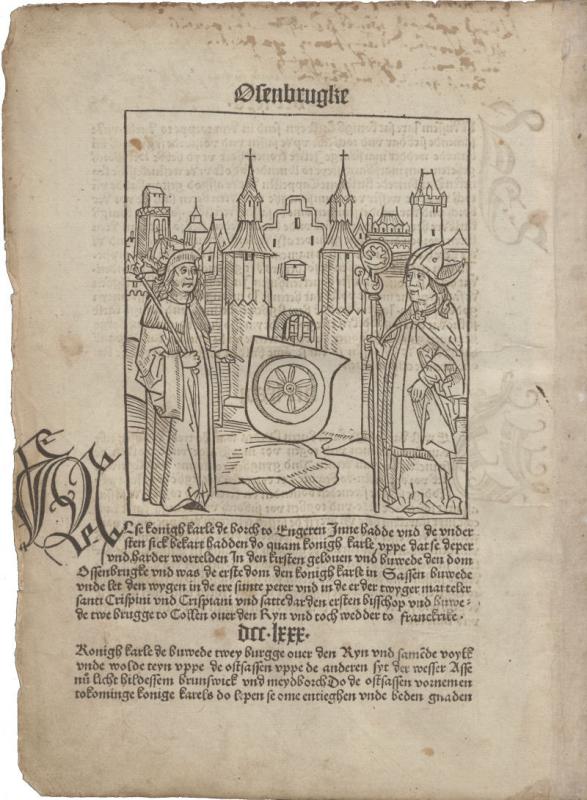

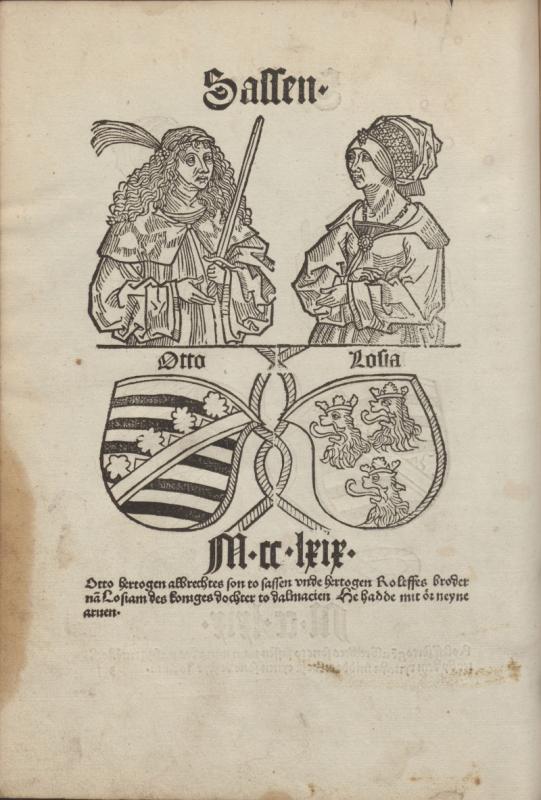

Some books were also more heavily illustrated, with as many as 500 or even more illustrations. The engravings were intended not only to decorate the book, but also to provide additional information. However, they were not too informative. More often they were just illustrations. Often the same engravings would contain illustrations of different cities, plants, real or fictional animals.

LMAVB RSS I-16

ISTC ic00488000, GW 04963

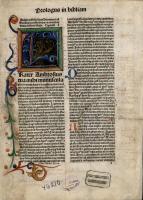

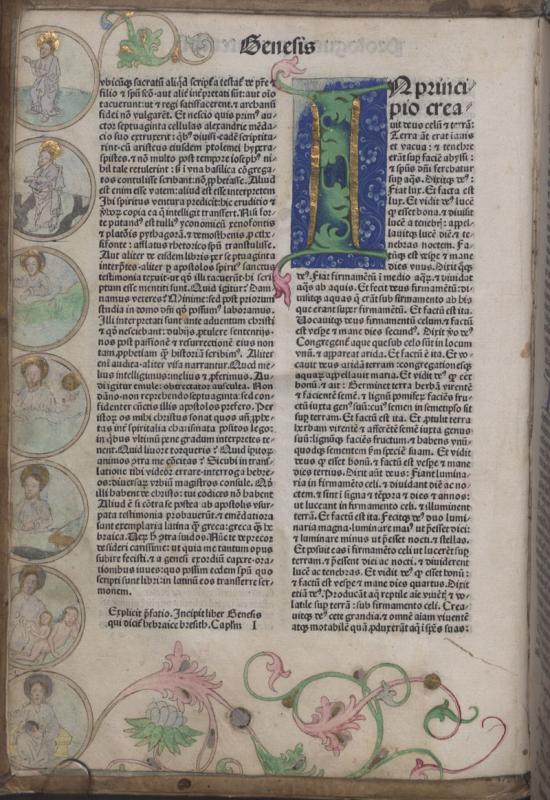

As already mentioned, one of the distinctive features of incunabula is that some of the books were additionally decorated (some simply, others luxuriously). This was particularly true when speaking about some of the larger, more expensive books, which were bought not only for reading, but also because an educated owner of the books wanted to add them to a personal collection in order to demonstrate to others their understanding, knowledge, and ability to build up a personal library. It is likely that no one paid to have a grammar book, a catechism or a novel illustrated. After all, these inexpensive books were simply thrown away after they had been “read” and their paper was reused. This is also evidenced by the fact that very few of these books have survived, and sometimes they are known only from descriptions. More expensive, more important books were treated differently. Bibles, for example, were more often decorated and with much greater care.

LMAVB RSS I-13

ISTC ib00566000, GW 04241

A slightly more lavishly decorated copy of the same Bible in the Bavarian National Library:

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Ink B-437

ISTC ib00566000, GW 04241

The quality of the illustrations printed in the book itself, or at least some of them, may have varied as well: some more carefully coloured, some less. The complexity of the project, the materials (the miniatures are decorated in different colours of paint or even gild) and the style are a testimony to the financial means of their owners, to their taste and to the medieval tradition of manuscripts, which was still alive at the time, and which is still more or less visible in the earliest printed books.

LMAVB RSS I-15

ISTC ie00084780, GW M34139

The printed book was eventuallytaken to a bookbinder, who would bind it according to the customer's taste and financial means. Bindings are not discussed in this exhibition. It is a separate topic. Some books have managed to preserve their original covers quite well, while others have become worn over time or have lost parts of the binding or even parts of the cover boards. Still, others have later been rebound. Thus, bookbinding, although an integral part of the process of turning a text into a book, deserves its own story and a different approach.